Have you ever picked up a prescription and seen a price that made you pause? Maybe it was $500 for a month’s supply of a drug your friend got for $30. You might wonder: why doesn’t a cheaper generic version exist? It’s not that no one tried. It’s that the system is built to block them - sometimes legally, sometimes technically, and often both.

Patents Are the First Wall

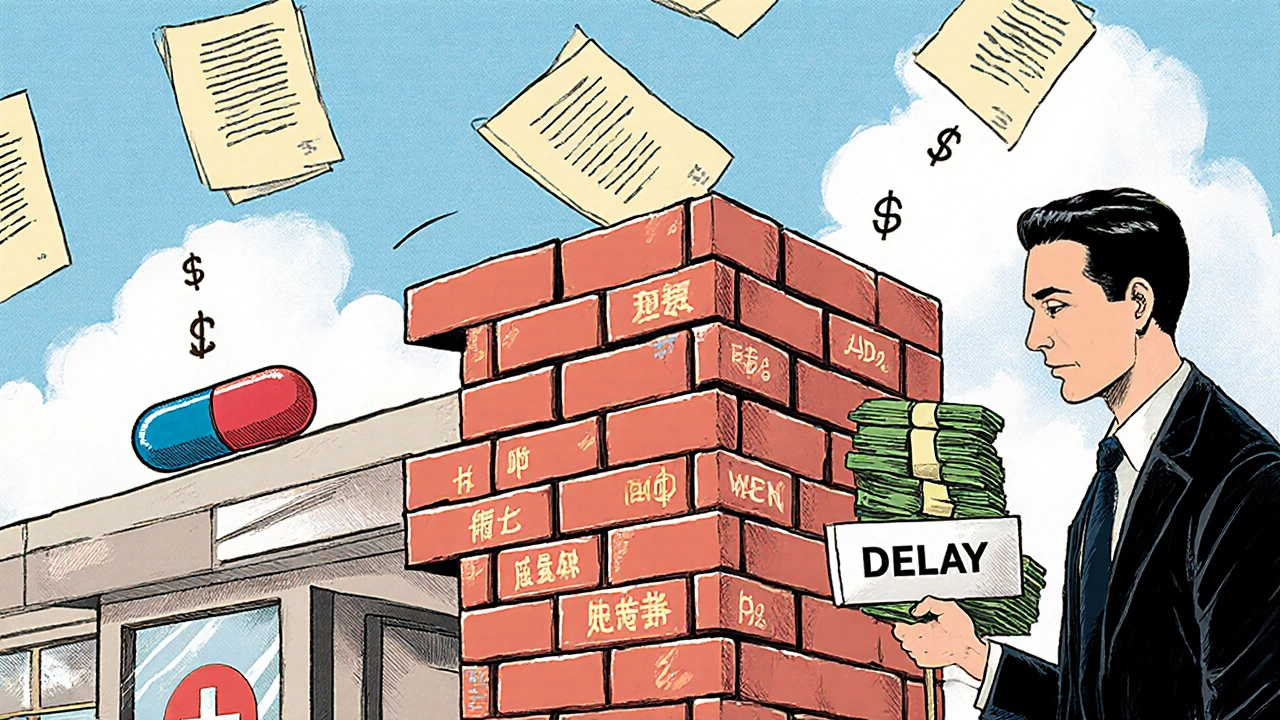

When a drug company invents a new medicine, they file a patent. That patent gives them 20 years of exclusive rights to sell it. That’s the law. But here’s the catch: the 20 years starts when the patent is filed - not when the drug hits the market. By the time a drug clears clinical trials, gets FDA approval, and hits pharmacy shelves, it’s already been 7 to 10 years into that clock. That leaves maybe 10 to 13 years of real monopoly time. Companies know this. So they stack patents like bricks. Take Nexium, the acid reflux drug. Its active ingredient, esomeprazole, was actually just a slightly tweaked version of the older drug Prilosec. When Prilosec’s patent was about to expire, AstraZeneca filed new patents on the new form - and got an extra five years of exclusivity. That’s called “product hopping.” It’s legal. It’s common. And it keeps generics out for years after the original patent should’ve expired.Complex Drugs Can’t Be Copied Easily

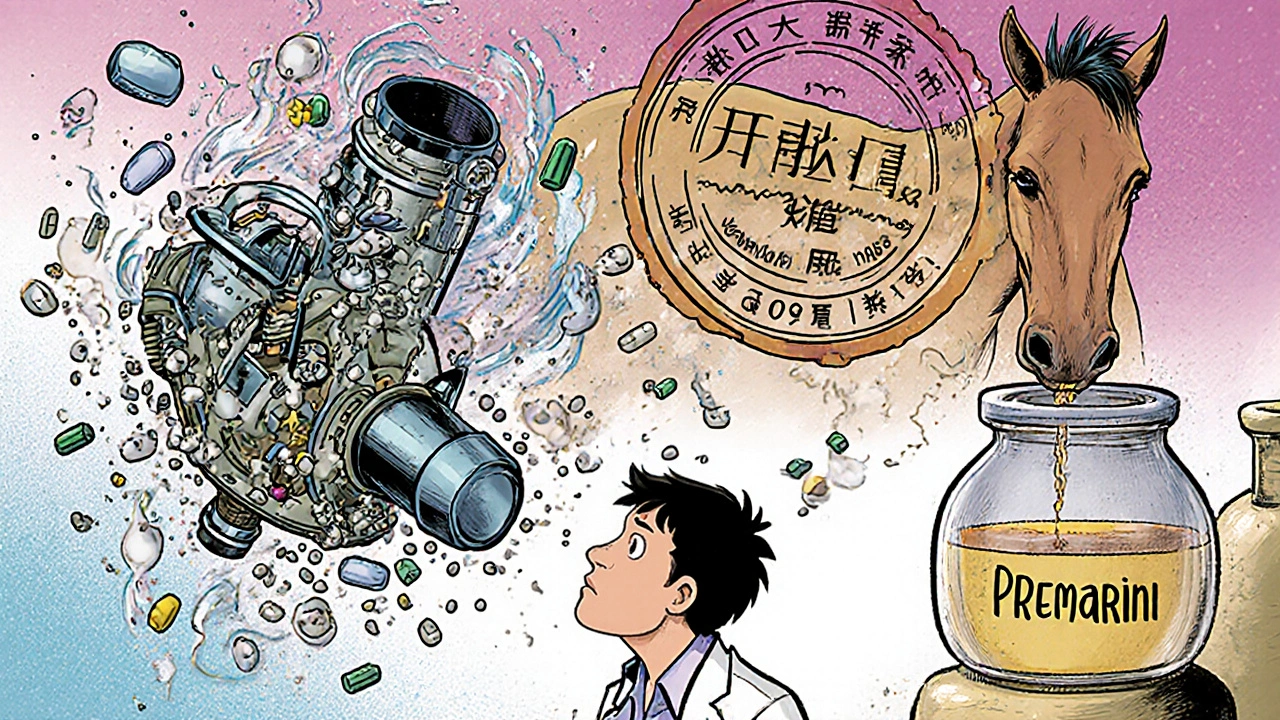

Not all drugs are made the same. Some are simple chemicals - like atorvastatin, the cholesterol drug once sold as Lipitor. Those are easy to copy. Generic makers can buy the same active ingredient, mix it with fillers, and slap it in a capsule. Done. But what about a drug like Premarin? It’s made from the urine of pregnant horses. It contains a mix of 10 or more estrogen compounds - many of which aren’t even fully identified. You can’t synthesize it in a lab. You can’t replicate the exact mix. So even though the patent expired decades ago, no generic has ever been approved. The FDA says: “We can’t prove it’s the same.” And without that proof, no generic can be sold. Same goes for inhalers like Advair Diskus. The active ingredients are known. But the way the drug is delivered - the exact particle size, the propellant, the way it sticks to the plastic chamber - affects how much actually reaches your lungs. Change the design even a little, and the drug might not work the same. That means generic makers need to run expensive clinical trials just to prove their version is equivalent. Most won’t bother unless they’re sure they can make a profit.Biologics: The Next Frontier

Biologic drugs - like Humira, Enbrel, or insulin - are made from living cells. Not chemicals. Think of them like a complex protein recipe cooked inside a living organism. No two batches are exactly alike. That’s why you can’t make a “generic” biologic. You make a “biosimilar.” The rules for biosimilars are brutal. The FDA requires 12 years of data exclusivity before even considering a biosimilar. That’s not a patent. That’s a government-mandated monopoly. Humira’s patent expired in 2016. But the first biosimilar didn’t hit the U.S. market until 2023. Why? Because the manufacturer, AbbVie, filed over 250 patents around Humira - covering everything from dosing schedules to manufacturing methods. Courts kept blocking competitors. It took seven years just to get one biosimilar approved. And insulin? Still mostly brand-name. Even though the active ingredient has been around since the 1920s, modern insulin formulations are protected by layered patents. The first biosimilar insulin didn’t arrive until 2021. And even then, it cost nearly $100 per vial - still way above what generics usually cost.

Manufacturing Is a Minefield

Even if a drug isn’t complex, making a generic version can be a nightmare. Take extended-release pills - like Prozac Weekly. The drug is slowly released over days. To do that, the pill has a special coating, a specific matrix, maybe even tiny pellets inside. Change the coating thickness by 5%, and the drug hits your bloodstream too fast or too slow. That’s dangerous. The FDA requires generic makers to prove their version behaves identically in the body. That means running expensive bioequivalence studies. For some drugs, the cost to develop a generic is $10 million or more. If the market is small - say, a drug used by only 10,000 people a year - no generic company will invest. It’s not worth it.Pay-for-Delay Deals: The Secret Handshake

Here’s the darkest part: sometimes, the brand-name company pays the generic company not to launch. It sounds insane. But it’s legal - for now. The FTC calls it “pay-for-delay.” The brand-name company offers the generic maker a deal: “Don’t launch your version. We’ll pay you millions to wait.” Between 1999 and 2012, there were 297 of these deals. One famous case involved the antidepressant Wellbutrin. The brand-name maker paid a generic company $100 million to delay their version for a year. That cost consumers an estimated $1 billion in extra drug costs. These deals are harder to pull off now thanks to court rulings and the CREATES Act (2019), which forces brand-name companies to give generic makers access to the drug samples they need for testing. But they still happen - especially with high-profit drugs.

What Does This Mean for Patients?

The numbers don’t lie. A 2022 GoodRx report found that brand-name drugs without generics cost, on average, 437% more than their generic equivalents. Medicare beneficiaries taking non-generic drugs spend over $5,000 a year out-of-pocket - more than double the cost of those with generics. Patients with chronic conditions like epilepsy, thyroid disease, or mental health disorders often worry: “Will the generic work the same?” For most drugs, yes. But for those with a narrow therapeutic index - where a tiny difference in blood levels can cause side effects or treatment failure - doctors sometimes stick with the brand. That’s not always about science. Sometimes it’s about fear. One Reddit user with chronic myeloid leukemia paid $14,500 a month for Gleevec before its generic arrived in 2016. After? $850. That’s a 94% drop. But for drugs like EpiPen, the price stayed sky-high for years - not because no one could copy it, but because Mylan kept making tiny design changes to reset the patent clock.What’s Changing?

The tide is turning - slowly. The FDA approved 27% more complex generics in 2022 than in 2021. Biosimilar approvals are expected to jump from 32 in 2022 to 75 by 2025. The CREATES Act is helping. The FTC is watching. But here’s the hard truth: about 5% of drugs - mostly ultra-complex biologics, orphan drugs for rare diseases, or those with impossible-to-replicate delivery systems - will likely never have true generics. That’s not a flaw in the system. It’s a feature. The system was designed to reward innovation. But now, it’s also being used to lock in profits.What Can You Do?

If you’re paying full price for a brand-name drug, ask your pharmacist or doctor: “Is there a generic?” Even if one isn’t listed, ask if there’s a similar drug that’s cheaper. Sometimes, switching from Viibryd to sertraline - both antidepressants - saves hundreds a month with no loss in effectiveness. Check the FDA’s Orange Book. It lists every patent and exclusivity period for branded drugs. You can find out when a drug might finally go generic. And if you’re on Medicare or private insurance, ask about prior authorization or patient assistance programs. Some manufacturers offer discounts if you can’t afford the brand. The system is stacked. But you’re not powerless.Why can’t generic companies just copy any drug once the patent expires?

They can - if the drug is simple. But many drugs have complex formulas, delivery systems, or are made from biological materials that can’t be perfectly replicated. The FDA requires generics to prove they work the same way in the body. For things like inhalers, biologics, or drugs made from animal sources, that proof is either impossible or too expensive to get.

Do generic drugs work as well as brand-name ones?

For most drugs, yes. The FDA requires generics to be within 80%-125% as effective as the brand in how they’re absorbed by the body. That’s a very tight range. But for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows - like seizure meds or thyroid pills - some patients and doctors prefer the brand because small differences can matter. That doesn’t mean the generic doesn’t work - just that the margin for error is slim.

How long does it take for a generic to appear after a patent expires?

It can take anywhere from days to years. Simple drugs? Sometimes generics launch the same day. Complex drugs? Often 3-7 years later. Why? Legal battles, patent thickets, pay-for-delay deals, or manufacturing challenges. The average delay for top-selling drugs is about 3.2 years beyond patent expiry, according to Harvard Medical School research.

Are there any drugs that will never have generics?

Yes. About 5% of medications - mostly ultra-complex biologics, orphan drugs for rare diseases, or those with proprietary delivery systems that can’t be copied - are unlikely to ever have true generic versions. Examples include certain insulin formulations, some cancer drugs, and drugs made from biological sources like Premarin. These are not just expensive - they’re technically impossible to replicate exactly.

Can I ask my doctor to switch me to a cheaper alternative?

Absolutely. Many drugs have different brand names or entirely different classes that work just as well. For example, if you’re on Viibryd (vilazodone) and it’s expensive, your doctor might switch you to sertraline - a generic SSRI with similar results. Pharmacists often help with these swaps. Don’t be afraid to ask: “Is there a cheaper option that works the same?”

11 Comments

Why pay $500 when you could pay $30? Simple answer: greed. The system is rigged and everyone knows it. No one’s surprised anymore.

I’ve been on a drug that had no generic for years. I watched the price climb from $200 to $1,400 while my insurance kept raising my copay. I didn’t even know what a biosimilar was until my pharmacist explained it. This isn’t just about money-it’s about dignity.

It’s heartbreaking to see how innovation has been twisted into exploitation. The original intent of patents was to encourage development-not to create decades-long monopolies through legal gymnastics. We need structural reform, not just bandaids. And yes, the FDA is trying, but they’re outgunned by corporate lawyers with more resources than most countries.

USA thinks it’s the best at everything… except making medicine affordable. In India, we get generics for 1/10th the price-even for complex drugs. Why? Because we don’t let corporations hold the whole world hostage. 🤷♀️

Let me be perfectly clear: this is not a market failure. This is a moral failure. The pharmaceutical industry has weaponized intellectual property law, regulatory loopholes, and patient desperation to extract wealth from suffering. And yet, we are told to be grateful for the ‘innovation.’ What innovation? Repackaging old molecules? Patenting horse urine? This is not capitalism. This is feudalism with a corporate logo.

People act like this is new. It’s not. The same companies did this with HIV meds in the 90s. Same playbook. Same excuses. Same profits. We’re just better at documenting it now. And guess what? Nothing changes. Because the people who profit aren’t the ones paying.

Do you realize that some of these drugs cost less to produce than a Starbucks latte? Like, seriously-$14,500 a month for a pill? That’s not a business. That’s a robbery with a white coat. And the worst part? The people who made these drugs didn’t even invent them-they just bought the rights and raised the price. No sweat. No risk. Just greed.

Oh no, the rich can’t afford their own medicine anymore? Cry me a river. You think the drug companies are the villains? No. It’s you. You let them get away with this. You don’t vote. You don’t protest. You just complain on Reddit. Wake up.

Back home in India, we have generics for almost everything-even for insulin. But here’s the twist: we don’t have the same access to healthcare. So while the price is low, the system still fails people. Maybe the answer isn’t just cheaper drugs… but better systems.

Biologics are not drugs. They are biological artifacts. You cannot replicate a living system. The FDA’s 12-year exclusivity is not excessive-it is scientifically necessary. The real issue is that patents are being used as economic weapons, not innovation shields.

It’s not about whether generics can be made. It’s about whether society values life over profit. If we truly believed in healing, we’d make these drugs affordable by law. Not because it’s fair. But because it’s human.

Write a comment