Most people assume that once a drug is approved, the company has 20 years of exclusive sales rights. That’s not true. The 20-year patent clock starts ticking long before the drug even hits shelves - often during early clinical trials. By the time a drug gets FDA approval, half the patent term may already be gone. That’s why some life-saving medications lose patent protection just 7 or 8 years after launch, while others stretch to 12 or 13. If you’re wondering why your prescription suddenly costs 80% less, or why a new generic hasn’t appeared yet, the answer lies in the messy, hidden math behind drug patents.

How the 20-Year Patent Term Actually Works

The U.S. patent system gives drugmakers a 20-year monopoly from the earliest filing date of the patent application. This rule was set in 1994 under international trade agreements. But here’s the catch: drug development takes years. On average, it takes 10 to 12 years from patent filing to FDA approval. That means the clock is running while researchers are testing safety, running clinical trials, and filling out paperwork. By the time the drug is ready to sell, maybe only 8 to 10 years of patent life remain.

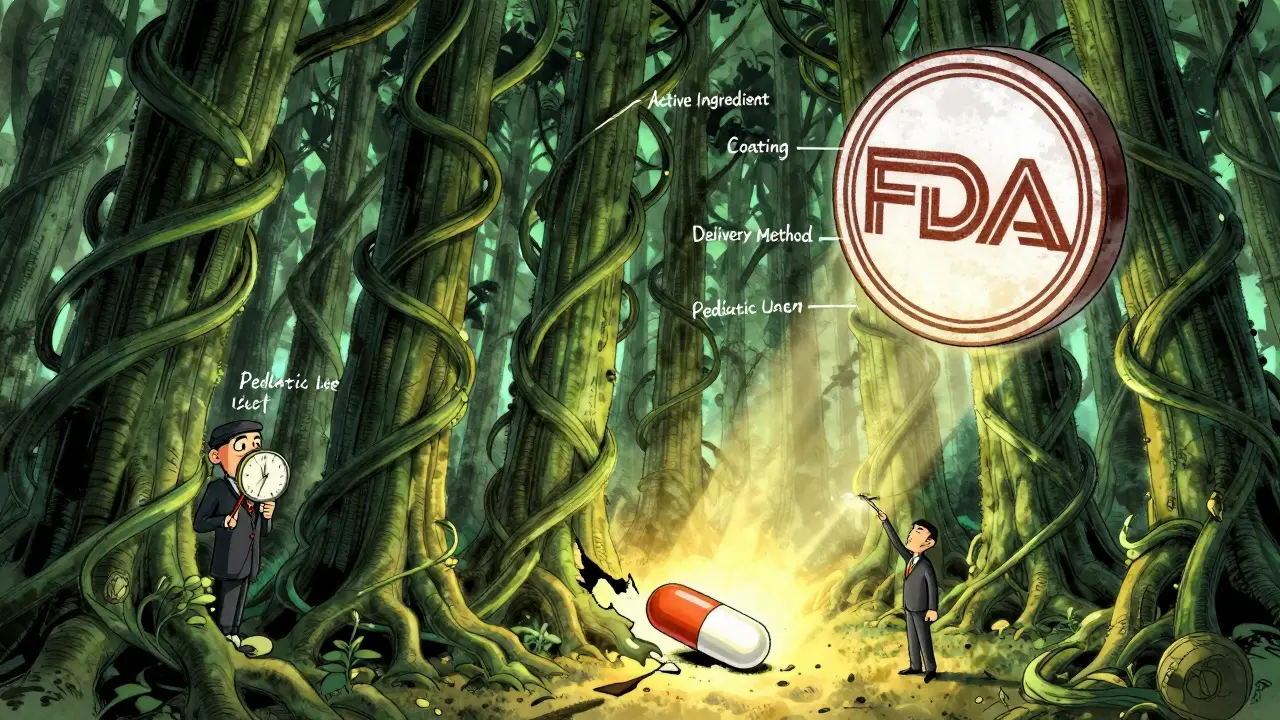

Take Humira (adalimumab), for example. Its core patent was filed in 1996. It got FDA approval in 2002. That left just 14 years of protection - but because of multiple secondary patents, the last one didn’t expire until 2023. That’s not unusual. Most blockbuster drugs rely on a patent thicket - dozens of overlapping patents covering the active ingredient, pill coating, delivery method, and how it’s used. Each one has its own 20-year term. So even if the main patent expires, other patents can keep generics out.

Why You Don’t Get 20 Years of Market Exclusivity

Patent time isn’t the same as market exclusivity. The FDA gives extra protection on top of patents. These are called regulatory exclusivities, and they’re separate from patent law. Here’s how they stack up:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: 5 years. During this time, the FDA can’t even review a generic version, even if the patent has expired.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity: 7 years for drugs treating rare diseases (under 200,000 patients in the U.S.).

- New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity: 3 years if a new dosage, indication, or formulation requires new clinical trials.

- Pediatric Exclusivity: 6 months added to any existing patent or exclusivity period if the company does extra studies on how the drug affects children.

These aren’t optional. Companies have to apply for them. And they’re often layered. A drug might get 5 years of NCE exclusivity, then 6 more months for pediatric studies, and still have 8 years left on its patent. That means the drug stays protected for 13+ years - even though the patent was filed 20 years ago.

The Hidden Clock: Patent Term Adjustment and Extension

Not all delays are the company’s fault. If the USPTO takes too long to approve the patent, the law says they owe time back. This is called Patent Term Adjustment (PTA). For example:

- If the USPTO doesn’t issue the first office action within 14 months, they owe you time.

- If the patent isn’t granted within 3 years of filing, they owe more time.

On average, PTA adds 2 to 4 years to a drug’s patent life. Some drugs get over 5 years extra. That’s why you’ll see expiration dates like 2031 on a drug filed in 2010.

Then there’s Patent Term Extension (PTE) - the real game-changer. Thanks to the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, drugmakers can apply for up to 5 extra years of patent life to make up for time lost during FDA review. But there’s a catch: the total time from FDA approval to patent expiration can’t exceed 14 years. So if a drug got approved 9 years after patent filing, it can get up to 5 years of extension - but only if it hasn’t already used up its 14-year limit.

And here’s where things get risky: companies have just 60 days after FDA approval to apply for PTE. Miss that window? You lose it forever. Many small biotechs miss it because they don’t have legal teams ready. Big pharma? They have entire departments dedicated to this.

How Generic Drugs Finally Get In

When the last patent or exclusivity period ends, generics can enter. But they don’t always rush in. The first generic company to file an application gets 180 days of exclusivity - meaning no other generics can enter during that time. That’s why you might see one generic version appear, then nothing for months. The first filer is banking on selling at a discount before others jump in.

But sometimes, the innovator company files a lawsuit. If they do it within 45 days of the generic applicant’s notice, the FDA must delay approval for 30 months. That’s a common tactic. In fact, 62% of pharmaceutical patents filed between 2019 and 2023 were challenged in court. The average lawsuit lasts 37 months. That’s longer than most patents last after approval.

And it’s not just pills. Biologics - complex drugs made from living cells - face even longer delays. Their generics, called biosimilars, take years to get approved. Even after approval, doctors and insurers are slow to switch. That’s why Humira’s biosimilars only grabbed about 40% of the market two years after launch.

What Happens When the Patent Expires?

Price drops are dramatic. For small-molecule drugs (like statins or blood pressure pills), prices typically fall 60-80% in the first year after generics arrive. Within 18 months, generics control 90% of the market. A 2022 study of Eliquis (apixaban) showed that after patent expiration, the average wholesale price dropped 62% in one year.

But here’s the twist: sometimes, the generic version costs more than the brand. Why? Because insurance companies might still prefer the brand if it’s covered under a special tier. One patient reported their copay jumped from $50 to $200 after the brand lost patent protection - because their insurer hadn’t updated their formulary yet. That’s not a pricing issue. It’s a system glitch.

Big pharma doesn’t just wait to be knocked out. They use lifecycle management - reformulating the drug, changing the delivery method, adding a companion diagnostic, or combining it with another drug. Take Tagrisso (osimertinib). The original patent expired in 2026, but new patents on its delivery system and use in combination therapy extend protection until 2033. That’s how companies keep revenue flowing.

What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond

The system is under pressure. The global pharmaceutical industry will lose $268 billion in revenue between 2023 and 2028 due to patent expirations. 2025 is the peak year - $62 billion in losses. That’s why companies are filing more patents on minor changes. The FTC found that some firms file secondary patents on packaging or dosing schedules just to delay generics by 2-3 years.

Legislators are pushing back. A bill introduced in early 2024 would eliminate some patent term adjustments, cutting exclusivity by 6-9 months. The USPTO is also rolling out automated systems to speed up PTA calculations - which could reduce delays and shorten patent life.

Meanwhile, the World Health Organization is calling for global patent terms to be reduced from 20 to 15 years to improve access. The pharmaceutical industry argues that the average R&D cost per drug is $2.3 billion - and without full protection, innovation will slow.

What You Need to Know

If you’re a patient, your best move is to ask your pharmacist: "Is there a generic?" and "When does the patent expire?" You might be paying more than you need to. If you’re on a fixed income, check if your insurer has a transition plan. Some switch to generics too late - leaving you stuck with high copays.

If you’re a caregiver or health advocate, track patent expirations for drugs you rely on. Sites like DrugPatentWatch and the FDA’s Orange Book list expiration dates. You don’t need to be a lawyer - just know that expiration dates aren’t fixed. They’re built from layers: patents, exclusivities, delays, lawsuits. And they change.

The bottom line: 20 years sounds long. But for most drugs, the real clock starts ticking before you’ve even heard the name. What looks like a long monopoly is often just a race against time - and the system is designed to give the drugmaker just enough to recover costs… and then let competition in.

Do all drug patents expire exactly 20 years after filing?

No. The 20-year term starts from the earliest filing date, but most drugs get FDA approval 10-12 years later. That leaves only 8-10 years of market exclusivity. Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) and Patent Term Extension (PTE) can add years, but the total time from FDA approval to expiration can’t exceed 14 years. Many drugs expire in 7-12 years after launch.

Can a drug stay protected longer than 20 years?

Yes - but not by extending the original patent. Companies file multiple patents covering different aspects: the active ingredient, how it’s made, how it’s taken, or how it’s used. Each has its own 20-year term. If one expires, another might still be active. This is called a "patent thicket." For example, Spinraza has patents protecting it through 2030, even though the first was filed in 2010.

Why do some generics appear years after patent expiration?

First, the innovator company might sue the generic maker. If they do so within 45 days of the generic’s notice, the FDA must delay approval for 30 months. Second, the first generic applicant gets 180 days of exclusivity - so others wait. Third, for biologics, biosimilar approval takes longer due to complex testing requirements.

What’s the difference between patent expiration and exclusivity?

Patents are legal rights granted by the USPTO. Exclusivity is a regulatory protection granted by the FDA. A drug can lose patent protection but still be protected by exclusivity - meaning no generic can be approved. For example, a new drug gets 5 years of exclusivity, even if the patent expires after 3 years. Generics can’t enter until both are gone.

How can I find out when a drug’s patent expires?

The FDA’s Orange Book lists all patents and exclusivity periods for brand-name drugs. You can search it online for free. Sites like DrugPatentWatch also provide public expiration dates. For complex drugs, look for multiple patents - expiration dates vary by type. Don’t rely on a single date. The last patent to expire is the real deadline.

What Comes Next?

If you’re managing a chronic condition and rely on a brand-name drug, start planning now. Talk to your doctor about alternatives. Ask your pharmacy if they’re tracking generics. Insurance companies often delay switching - so don’t wait for them to act. The next big wave of patent expirations hits in 2025-2027, with drugs like Humira, Eliquis, and Xarelto going generic. Prices will drop. But only if you’re ready for it.

11 Comments

Let me get this straight - the pharma companies file patents before the drug even exists, then stretch it out with 17 different patents on pill color and breathing instructions? This isn’t innovation. This is a legal loophole buffet. I get they need to recoup costs, but 20 years? More like 30 when you factor in PTA, PTE, and patent thickets. It’s a racket disguised as science. And don’t get me started on how they sue generics into oblivion just to keep prices high. The system is rigged, and we’re the ones paying for it.

I really appreciate how detailed this is. My mom’s on Humira and we had no idea why the price kept jumping even after "patent expiration." Turns out, it was another layer. This explains so much.

I just cried reading this. My brother died because we couldn’t afford his drug after the patent "expired" but before the generic came out. 18 months. That’s how long we waited. 18 months. And they had the nerve to call it "fair."

Yo this is wild. I work in a pharmacy and people come in all the time asking why their $300 pill is suddenly $40. We don’t even know half the stuff in this post. The patent thicket thing? Mind blown. I’ve been telling folks to check the Orange Book for years but no one listens. Now I’ve got ammo. Thanks for laying it out like this.

Oh sweet jesus. So the reason my insulin went from $50 to $200 after the "generic" came out is because my insurance company didn’t update their formulary? That’s not a glitch. That’s negligence. And they wonder why people hate the system? I’m not mad. I’m just disappointed. And honestly? I’m done trusting them.

This whole thing is a joke. You know what’s funny? They say "20 years" like it’s some noble limit. But in reality, most drugs are out by 8 years. So why do we act like they’re being robbed? They made 10x their money already. And don’t even get me started on those 60-day PTE windows. If you’re a biotech with 3 employees and no lawyer? Tough luck. Big Pharma has a whole team just to game the system. It’s not broken. It’s designed this way.

I’ve been following this for years. The FDA’s Orange Book? It’s a mess. The data’s outdated. The patents are listed in a way that makes no sense. And don’t even think about trying to search for biosimilars - half the time, the entry doesn’t even exist. The whole system is paper-based, slow, and designed to confuse. You think you’re getting transparency? You’re getting a maze.

This was super helpful. I didn’t realize patent term adjustment could add 5 years. That’s wild. I’m curious - if the USPTO is slow, why don’t they just speed up? Is it funding? Staff? Just wondering how fixable this is.

I’m a nurse and I see this every day. Patients get so confused when their copay jumps after a "generic" hits. They think it’s supposed to be cheaper, but then their insurance still charges them for the brand. It’s not the drug’s fault - it’s the system. I’ve started printing out the Orange Book entries for my patients. Just one page. Sometimes that’s all it takes to save someone $150 a month.

I’m not saying this is wrong, but... didn’t we already have this conversation in 2017? I swear I read this exact thing on Reddit. And now it’s back. Same stats. Same examples. Same outrage. And nothing changed. So what’s the point?

It is with profound respect for the complexity of pharmaceutical innovation that I acknowledge the extraordinary efforts undertaken by stakeholders to balance intellectual property rights with public health imperatives. The interplay between statutory frameworks, regulatory mechanisms, and commercial incentives constitutes a remarkably nuanced ecosystem. One must recognize that the 20-year patent term, when augmented by statutory adjustments and exclusivities, is not an arbitrary construct, but rather a carefully calibrated instrument designed to incentivize high-risk, capital-intensive research. While market dynamics may appear inequitable to the lay observer, the structural integrity of this system remains indispensable to the continued advancement of therapeutic science.

Write a comment