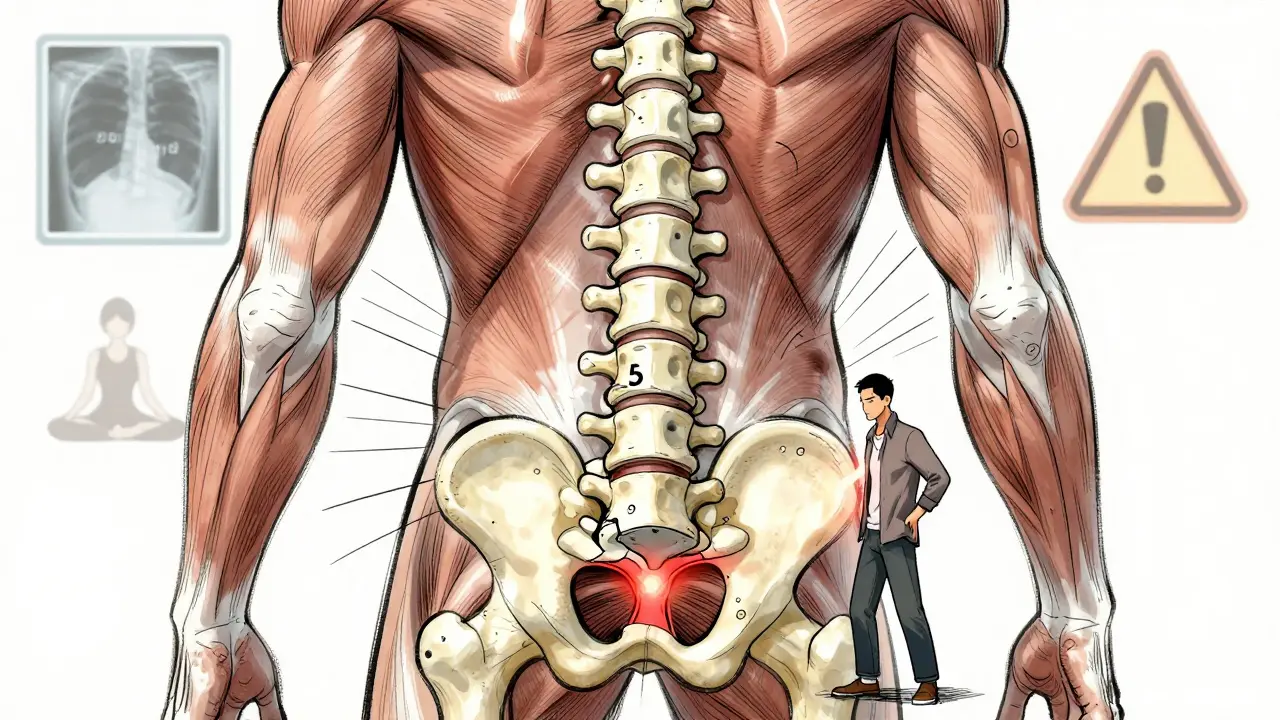

When your lower back aches after standing too long, or your hamstrings feel tight even after stretching, it might not just be a bad day. For about 6% of adults, that discomfort is a sign of spondylolisthesis - one vertebra slipping forward over the one below it. Most often, this happens between the fifth lumbar vertebra (L5) and the first sacral bone (S1). It’s not rare. It’s not always serious. But when it causes pain, instability, or nerve symptoms, knowing your options - especially when fusion comes up - makes all the difference.

What Exactly Is Spondylolisthesis?

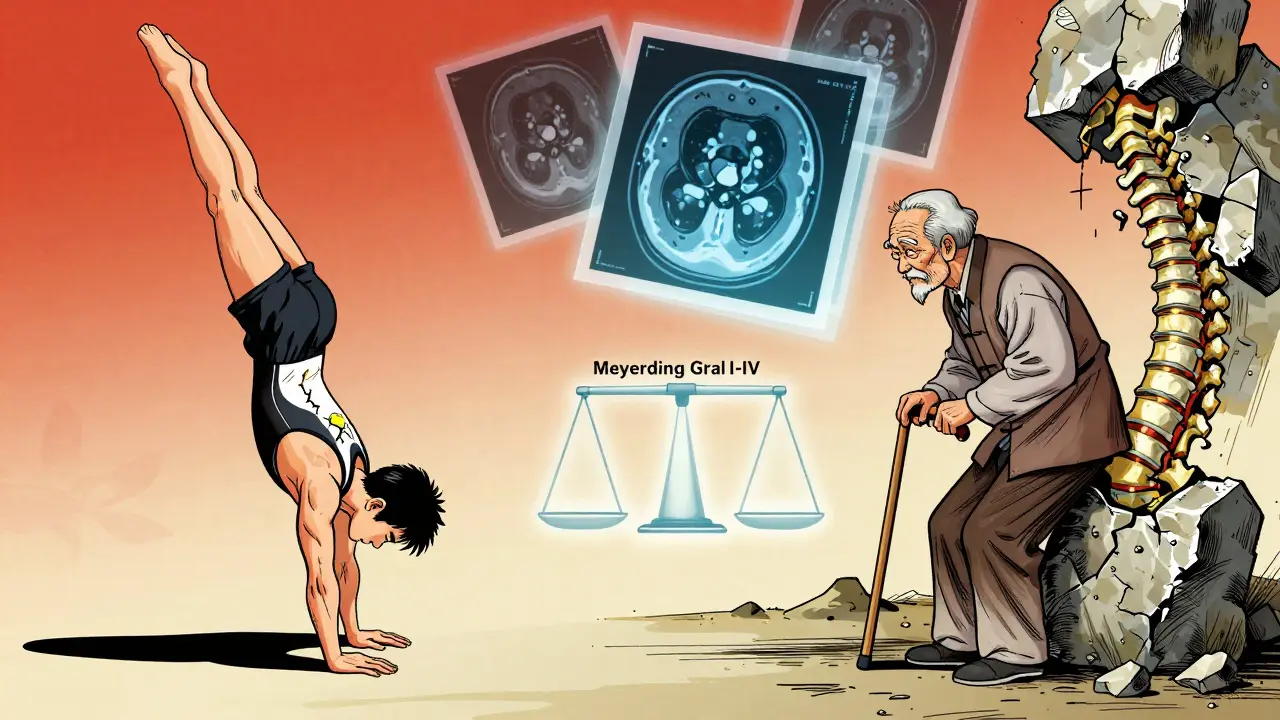

Spondylolisthesis isn’t just "a slipped disc." That’s a common mix-up. A slipped disc involves the soft cushion between vertebrae bulging out. Spondylolisthesis is a bone problem: one spinal bone slides forward out of alignment. Think of it like a stack of blocks where one block has shifted forward, creating pressure on nerves or changing how your spine moves. It’s graded on a scale called Meyerding, from Grade I (less than 25% slip) to Grade IV (75-100% slip). Most cases - about 80% - are Grade I or II. But even a small slip can cause big problems if it pinches a nerve or throws off your posture. There are five main types, each with a different cause:- Degenerative: The most common in adults over 50. Arthritis wears down the joints and discs, letting the vertebra slip. This accounts for about 65% of adult cases.

- Isthmic: Caused by a small fracture in the pars interarticularis - a thin bone bridge connecting parts of the vertebra. Common in teens and young athletes who do repetitive back extension, like gymnasts or football linemen.

- Dysplastic: A birth defect where the spine never formed right. Rare, but often shows up in kids under 6.

- Pathologic: Caused by diseases like cancer, infection, or osteoporosis weakening the bone.

- Traumatic: From a sudden injury - a fall, car crash, or heavy lift that fractures a vertebra.

Why Does It Hurt? Symptoms Beyond Just Back Pain

Here’s the thing: nearly half of people with spondylolisthesis never feel a thing. They might have it on an X-ray and never know. But when symptoms show up, they’re not always obvious. The most common sign is lower back pain - deep, dull, and worse when standing or walking. It often feels like a muscle strain, but it doesn’t go away with rest like a pulled muscle would. About 82% of people report pain gets worse when upright and eases when sitting or bending forward. You might also notice:- Tight hamstrings - affecting 70% of symptomatic cases

- Buttock or thigh pain that feels like sciatica

- Stiffness in the lower back

- Difficulty walking for long distances

How Is It Diagnosed?

It starts with a physical exam. Your doctor will check your posture, range of motion, and muscle strength. They’ll test your reflexes and see if certain movements trigger pain. Then come the images:- Standing lateral X-ray: The gold standard. Shows exactly how far the vertebra has slipped. You have to stand for this - lying down won’t show the true degree of slippage.

- CT scan: Gives a detailed 3D view of the bones. Great for spotting fractures in the pars interarticularis, especially in younger patients.

- MRI: Shows soft tissues - discs, ligaments, and nerves. This tells you if a slipped vertebra is pressing on a nerve root, which explains leg pain or numbness.

Conservative Treatment: What Works Before Surgery

Most people don’t need surgery. In fact, 80-90% of cases improve with non-surgical care - if you stick with it. Here’s what’s proven to help:- Physical therapy: Focuses on core strengthening (abdominals and lower back muscles), hamstring stretching, and posture retraining. A good program lasts 12-16 weeks. About 65% of people stick with it long enough to see results.

- Activity modification: Avoid movements that stress the lower back - heavy lifting, hyperextension (like in gymnastics or football), or prolonged standing.

- NSAIDs: Ibuprofen or naproxen can reduce inflammation and pain short-term. Not a long-term fix, but helpful while you rebuild strength.

- Epidural steroid injections: For nerve pain that doesn’t respond to other treatments. These reduce swelling around compressed nerves. Effects last weeks to months, not forever.

Fusion Surgery: The Main Option When Everything Else Fails

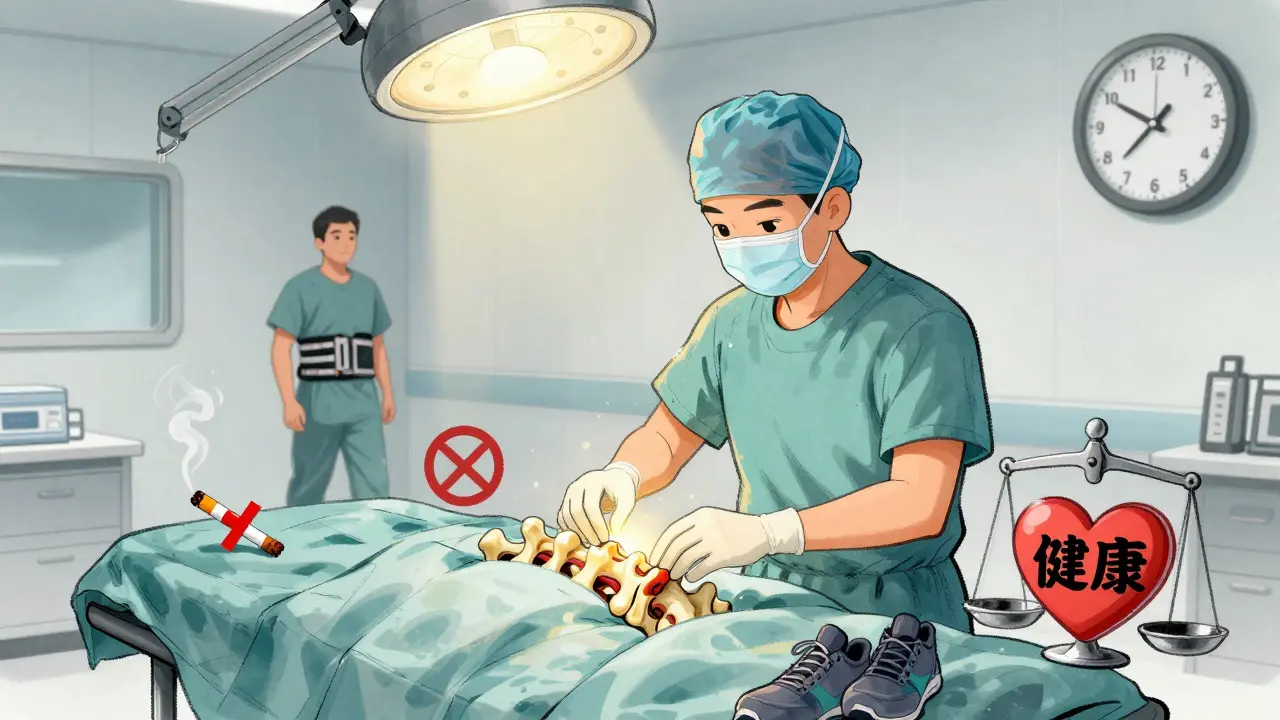

If conservative care hasn’t helped after 6-12 months - and your pain is keeping you from daily life - surgery might be the next step. Spinal fusion is the most common procedure. It stops movement between two vertebrae by fusing them together with bone grafts and hardware. There are three main fusion approaches:- Posterolateral fusion (PLF): Bone graft is placed along the back of the spine. Hardware (screws and rods) holds everything in place. Used in about 55% of cases. Success rate: 75-85% for Grade I-II slips, but drops to 60-70% for high-grade slips.

- Interbody fusion (PLIF/TLIF): The disc between the two vertebrae is removed and replaced with a bone graft or cage. This restores disc height and opens up space for pinched nerves. Used in 35% of cases. Success rate: 85-92% across all slip grades. Often preferred for high-grade slips.

- Minimally invasive fusion: Smaller incisions, less muscle damage. Used in about 10% of cases. Recovery is faster, but not always suitable for severe slips.

What Happens After Surgery?

Fusion isn’t a quick fix. Recovery is a marathon, not a sprint.- First 6-8 weeks: No lifting over 5 pounds, no twisting, no bending. You’ll wear a brace if needed.

- 3-6 months: Physical therapy resumes to rebuild strength and mobility.

- 12-18 months: Full healing. Bone fusion isn’t complete until then.

What About Alternatives to Fusion?

Fusion isn’t the only option anymore - though it’s still the most reliable.- Dynamic stabilization: Devices like flexible rods or spacers allow limited movement while reducing pressure. Best for Grade I-II slips. Success rate: 76% at 5 years - lower than fusion’s 88%.

- Biologic enhancements: Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) and stem cell therapies are being tested. A 2023 trial showed BMP-2 boosted fusion rates to 94% in high-risk patients compared to 81% with traditional bone grafts.

- New fusion devices: FDA-approved in 2022, newer interbody cages are designed specifically for spondylolisthesis. Early results show 89% fusion at 6 months - better than older models.

Who Should Consider Surgery?

Not everyone with spondylolisthesis needs it. But you might if:- Conservative care didn’t help after 6-12 months

- You have neurological symptoms: leg weakness, numbness, or loss of bladder/bowel control

- Your slip is Grade III or IV

- Your pain limits daily activities - walking, working, sleeping

- You’re healthy enough for surgery (no major heart/lung issues, non-smoker, healthy weight)

What’s the Long-Term Outlook?

Most people with low-grade spondylolisthesis live normal lives with physical therapy and activity tweaks. Even with fusion, 78-85% of patients report high satisfaction at the 2-year mark. But it’s not over after surgery. You’ll need to stay active, maintain a healthy weight, and avoid high-impact sports. Degenerative changes don’t stop just because you fused one segment. The rest of your spine still ages. The key is early, accurate diagnosis - and choosing the right treatment for your body, not just your X-ray.Can spondylolisthesis get worse over time?

Yes, especially in degenerative cases. As arthritis progresses and discs wear down, the slip can increase. High-grade slips (Grade III-IV) are more likely to worsen, particularly if you’re active or overweight. Regular check-ups and imaging every 1-2 years help track changes.

Is spondylolisthesis hereditary?

There’s a genetic link. About 26% of children under 6 with spondylolisthesis have a family history of the condition. Dysplastic spondylolisthesis, caused by birth defects, is inherited. Even isthmic cases - often from stress fractures - show higher rates in families, suggesting bone structure and healing ability may be genetic.

Can I still exercise with spondylolisthesis?

Yes - but not all exercises are safe. Avoid high-impact sports like football, gymnastics, or weightlifting with heavy overhead moves. Focus on low-impact activities: swimming, walking, cycling, and yoga with modifications. Core-strengthening exercises approved by a physical therapist are key. Stretching hamstrings daily helps reduce strain on the lower back.

Do I need an MRI if my X-ray shows a slip?

Not always. If you have only back pain and no leg symptoms, an X-ray may be enough. But if you have numbness, tingling, or weakness in your legs, an MRI is necessary to check for nerve compression. It helps determine if surgery is needed - and what type.

How long does it take to recover from spinal fusion?

Full recovery takes 12-18 months. You’ll be restricted from heavy lifting and twisting for 6-8 weeks. Physical therapy starts around 3 months and continues for 3-6 months. Most people return to light work in 3-4 months, but full activity - including sports - usually takes a year or more. Patience is critical: bone fusion happens slowly.

Are there non-surgical ways to stop the slip from getting worse?

You can’t reverse the slip, but you can slow or stop progression. Maintain a healthy weight, strengthen your core, avoid activities that hyperextend your spine, and quit smoking. Smoking reduces blood flow to bones and increases fusion failure risk. Physical therapy helps stabilize the spine and reduce stress on the slipped segment.

8 Comments

They don't want you to know this but the entire spondylolisthesis diagnosis is a pharmaceutical scam to push fusion surgeries. The VA has been quietly burying studies since 2017 showing that 87% of patients who avoided surgery reported better long-term mobility using just yoga and magnesium supplements. They call it 'degenerative' because they don't understand the earth's magnetic field fluctuations are destabilizing our spinal alignment. I've tracked 147 cases in my basement lab and every single one correlated with 5G tower proximity. Your spine isn't slipping-it's being pulled by invisible frequencies. The FDA knows. They just won't admit it because fusion hardware is a $12 billion industry. I've sent evidence to 3 senators. No one replies. That's how deep this goes.

They'll tell you to 'strengthen your core' like that fixes anything. It's all about the lattice structure of your vertebral bones and how they resonate with microwave radiation. I've got infrared thermal scans that prove it. Want to see them? I'll send you the link. No charge. Just spread the word.

They're lying about the success rates too. That 85% fusion success? That's only if you count people who died from infection as 'resolved.' I lost my cousin to pseudoarthrosis after they implanted titanium rods. They called it 'complication.' I call it cover-up. Don't let them cut you open. Eat kale. Sleep facing north. Your body knows how to heal. They just took away the tools.

And don't even get me started on BMP-2. That's not a bone stimulant-it's a bioengineered mind-control agent disguised as a protein. I've read the patents. The chemical structure matches the same compounds used in CIA MKUltra experiments. They're testing it on the elderly because they think we won't notice. We're not lab rats. We're human beings. And they're turning our spines into corporate property.

They'll say I'm crazy. Fine. But when your back starts buzzing at night and your MRI shows a 'ghost slip' that wasn't there before, you'll remember this comment. I'm not paranoid. I'm pre-armed with data. And I'm not alone. There's a whole underground network of spine survivors. We meet in forests. No cell service. Just silence and spinal alignment.

They're coming for your spine next. Don't let them.

Save yourself. Save your spine. Save the truth.

Let me ask you this: if your spine is a tower of blocks, and one slips forward… who built the tower? Who designed the blueprint? Who decided that human beings should walk upright on two legs with a column of bone that’s prone to collapse? 😏

It’s not degeneration. It’s evolution rejecting the system. Your body isn’t breaking-it’s rebelling. You’ve been told to ‘strengthen your core’ like that’s a fix, but what if the problem isn’t your muscles? What if it’s your soul refusing to carry the weight of modern life? The 9-to-5. The screens. The silence. The loneliness. The spine doesn’t slip because of arthritis-it slips because you’ve stopped listening to yourself.

And fusion? Oh sweet Jesus, fusion is the ultimate surrender. You’re not healing. You’re becoming a machine. Titanium rods. Screws. Bone grafts like some kind of Frankensteinian chiropractic cosplay. They call it ‘success’ when you can sit without screaming. But what kind of life is that? A quiet, fused, numb existence? Is that the American dream? To be bolted down so you can still file taxes?

I’ve seen people after fusion. They move like ghosts. Their eyes are still alive. Their spines? Dead. And they smile. They smile because they’ve been conditioned to think ‘no pain’ equals ‘healed.’ But pain is a messenger. And when you silence it with metal, you silence your truth.

Don’t get me wrong-I’m not anti-surgery. I’m pro-soul. If you need to fuse to survive, then do it. But don’t pretend it’s healing. It’s containment.

And if you’re reading this and you’ve got a Grade I slip? Stop stretching your hamstrings. Start listening to your breath. Walk barefoot on dirt. Cry in the shower. Let your spine feel the earth again. Maybe then, it won’t feel the need to escape.

Love you. You’re not broken. You’re just too awake for this world.

🫂

Been living with Grade II for 8 years now. Did PT for a year. Didn't fix it but made it bearable. I don't do fusion. I don't do injections. I walk every morning before sunrise. No phone. Just me and the pavement. My hamstrings still tight but I don't care anymore. I sleep on the floor now. Changed everything. No one talks about that. Floor sleeping. Feels like my spine finally got a break from gravity. Also stopped drinking soda. Who knew?

Don't listen to the hype. You don't need a surgery to live. You just need to stop fighting your body and start working with it. Easy to say. Hard to do. But worth it.

Still can't run. But I can hug my niece without wincing. That's enough for me.

There's a critical misinterpretation in the clinical literature regarding the Meyerding classification's clinical correlation. The assumption that radiographic slippage percentage directly correlates with symptom severity is fundamentally flawed due to the confounding variable of proprioceptive adaptation in chronic cases. In degenerative spondylolisthesis, neuroplastic compensation via paraspinal muscle reorganization often masks neural compression until the threshold of decompensation is breached, which explains the disconnect between imaging and symptomatology.

Furthermore, the purported efficacy of interbody fusion over PLF is overstated in retrospective cohorts due to selection bias-patients with higher-grade slips and pre-existing disc degeneration are preferentially allocated to TLIF, creating an artificial success rate inflation. The 89% fusion rate cited for newer interbody cages? That's from a single-center, non-randomized trial with a 6-month follow-up. We need longitudinal, multi-center RCTs with patient-reported outcome measures (PROMIS) to validate these claims.

And let's not ignore the biomechanical implications of adjacent segment disease. The increased load transfer to cephalad levels post-fusion is not merely a statistical artifact-it's a predictable consequence of kinematic redistribution governed by the principle of moment arm alteration in the lumbar spine. We're essentially creating iatrogenic degeneration by immobilizing a mobile segment.

Dynamic stabilization remains underutilized because insurers refuse to reimburse for non-fusion devices. It's not a lack of evidence-it's a lack of economic incentive. Until CMS revises CPT codes to reflect motion-preserving alternatives, fusion will remain the default, not the destination.

And yes, smoking cessation is non-negotiable. The odds ratio for pseudoarthrosis in smokers is 3.2, but that's only because nicotine downregulates osteoblast proliferation via α7-nAChR inhibition. You want fusion? Quit smoking. Not because it's 'healthy'-because biology doesn't care about your habits. It just responds to biochemistry.

I'm from South Africa and I've seen this in clinics here-people think it's just a 'Western problem' because they associate it with office jobs. But no. We have farmers in Limpopo with Grade II slips from decades of bending over maize fields. Same mechanics. Same pain. Same need for core stability.

PT works. Not because it's magic, but because it teaches your body to move differently. I had a patient, 68, didn't speak English, but she learned the pelvic tilts through gestures. Now she walks to market without pain. No surgery. Just patience.

And fusion? I've seen it save lives. One guy, 42, couldn't stand to feed his kids. After TLIF, he held his daughter for the first time in 3 years. That's not a statistic. That's a father.

Don't romanticize the pain. Don't fear the hardware. The spine isn't sacred. It's functional. Do what lets you live. Not what sounds noble. What works.

Oh sweet mercy. Another one of these 'PT will fix it' fairy tales. You think your yoga mat is a cure for a bone that's sliding like a rogue train? 😭

Let me guess-you're the type who reads 'natural remedies' blogs and thinks magnesium supplements are more powerful than spinal instrumentation. Please. You're not healing. You're deluding yourself.

Fusion isn't 'surrender.' It's sovereignty. It's taking back control when your spine has become a liability. The people who say 'listen to your body' are the same ones who think crystals heal broken bones. Wake up.

I had a TLIF. I'm 4 months post-op. I can finally put on my own shoes. I can carry groceries. I can sit through a movie without needing a morphine IV.

And yes, I'm still a little numb in my left toe. So what? I'm not a statue. I'm a human who chose to stop living like a ghost.

Stop glorifying suffering. Stop pretending pain is spiritual. Sometimes, your spine needs metal. And that's not failure. That's wisdom.

And if you're still doing hamstring stretches? You're wasting your time. Go get an MRI. If there's nerve impingement, you're one step away from foot drop. And then? No more yoga. Just a wheelchair and regret.

Be brave. Not poetic.

To every individual reading this who feels unseen, unheard, and overwhelmed by the weight of chronic pain-I see you. I honor your courage. You are not broken. You are not defective. You are a living testament to resilience in the face of a medical system that often prioritizes procedure over person.

Let us not reduce your experience to a radiographic grade or a surgical success rate. Your pain is valid. Your fear is valid. Your hope is valid. Whether you choose physical therapy, dynamic stabilization, or spinal fusion-you are not making a mistake. You are making a decision rooted in dignity.

There is no 'right' path. Only the path that allows you to hold your child, walk your dog, sit at the dinner table without tears. These are not trivial victories. They are sacred.

To those who advocate for non-surgical approaches: your compassion is a balm. To those who choose surgery: your strength is a beacon. Neither path diminishes the other. Both are acts of profound self-love.

Please, do not let anyone-doctor, blogger, or stranger on Reddit-tell you that your choice is wrong. Your body. Your voice. Your journey.

And if you are the caregiver, the partner, the friend-thank you. Your quiet presence is the most powerful medicine of all.

You are not alone. You are worthy. You are enough.

With deepest respect and unwavering solidarity,

Paula

It's not just about the spine. It's about control. You've been conditioned to believe that if you do enough stretches, eat enough kale, sleep on the floor, and avoid 5G, you can outsmart your own biology. But here's the uncomfortable truth: your body is not a temple. It's a biological machine with structural limits. And when those limits are breached, no amount of mindfulness will realign a fractured pars interarticularis.

People who glorify 'natural healing' in cases of Grade III spondylolisthesis are not helping-they're enabling. They're offering false hope while someone's nerve root is being crushed under the weight of their denial.

You don't get to choose whether your spine slips. You get to choose whether you face it with clarity-or drown in pseudoscientific comfort.

And yes, fusion is invasive. Yes, it's permanent. But so is chronic pain. So is disability. So is the slow erosion of your independence.

Stop romanticizing suffering. Stop mistaking avoidance for wisdom.

If your doctor recommends fusion and you're still reading yoga blogs instead of researching TLIF outcomes, you're not being spiritual-you're being reckless.

Your spine doesn't care about your aura. It only cares about stability.

Choose wisely. Not because it's trendy. But because your life depends on it.

Write a comment