Opioid Rotation Calculator

Current Opioid

Target Opioid

Morphine

Commonly used as a reference point for conversion. May cause significant nausea, drowsiness, and constipation.

Oxycodone

Often causes less nausea and constipation than morphine. May be easier on the digestive system.

Fentanyl (patch)

Avoids the digestive system entirely, which helps with nausea and stomach issues. Good option for patients with vomiting or gut motility problems.

Methadone

Can reduce total opioid dose by 30-50% while maintaining pain control. However, has a long half-life and can be unpredictable.

Important Safety Note

Opioid rotation requires careful medical supervision. This tool calculates a conversion but should never replace professional medical advice. Always follow your doctor's instructions and never adjust your dose without consulting a healthcare provider.

When opioids stop working the way they should, it’s not always because the pain is getting worse. Sometimes, it’s the medication itself causing the problem. Nausea that won’t quit. Drowsiness so heavy you can’t get out of bed. Constipation that feels impossible to manage. These aren’t just inconveniences-they can make life harder than the pain you’re trying to treat. That’s where opioid rotation comes in: switching from one opioid to another to cut side effects without losing pain control.

Why Switch Opioids at All?

Not everyone responds the same way to the same opioid. One person might tolerate morphine just fine. Another might get sick to their stomach with even a low dose. This isn’t about being "resistant" to opioids-it’s about how your body processes each drug differently. Opioid rotation isn’t a last resort. It’s a smart, evidence-backed move when side effects outweigh benefits. Research shows that between 50% and 90% of patients who switch opioids see real improvements-either less nausea, clearer thinking, or better pain control. The key is knowing when to make the move. Experts agree on clear triggers: when you’ve increased your dose by more than 100% and still can’t get pain under control, or when side effects like confusion, muscle twitching, or vomiting become unbearable.When Opioid Rotation Makes Sense

Opioid rotation isn’t for every situation. It’s not meant for sudden pain spikes or short-term flare-ups. It’s for people on long-term therapy who’ve hit a wall. Here are the real reasons clinicians recommend it:- You’re experiencing severe side effects-nausea, vomiting, dizziness, or delirium-that don’t improve with anti-nausea meds or dose tweaks.

- Your pain isn’t improving despite doubling or tripling your dose.

- You’ve developed new health issues like kidney or liver problems that make your current opioid harder to clear from your body.

- You need a different way to take the medicine-like switching from pills to a patch because swallowing is difficult.

- You’re taking other drugs that interact dangerously with your current opioid.

- You’ve been diagnosed with opioid-induced hyperalgesia-where the opioid itself makes your nerves more sensitive to pain.

One of the most misunderstood reasons is "poor opioid responsiveness." That phrase suggests you don’t respond to opioids at all. But that’s rarely true. It usually means you don’t respond well to that specific opioid. Switching to another one can change everything.

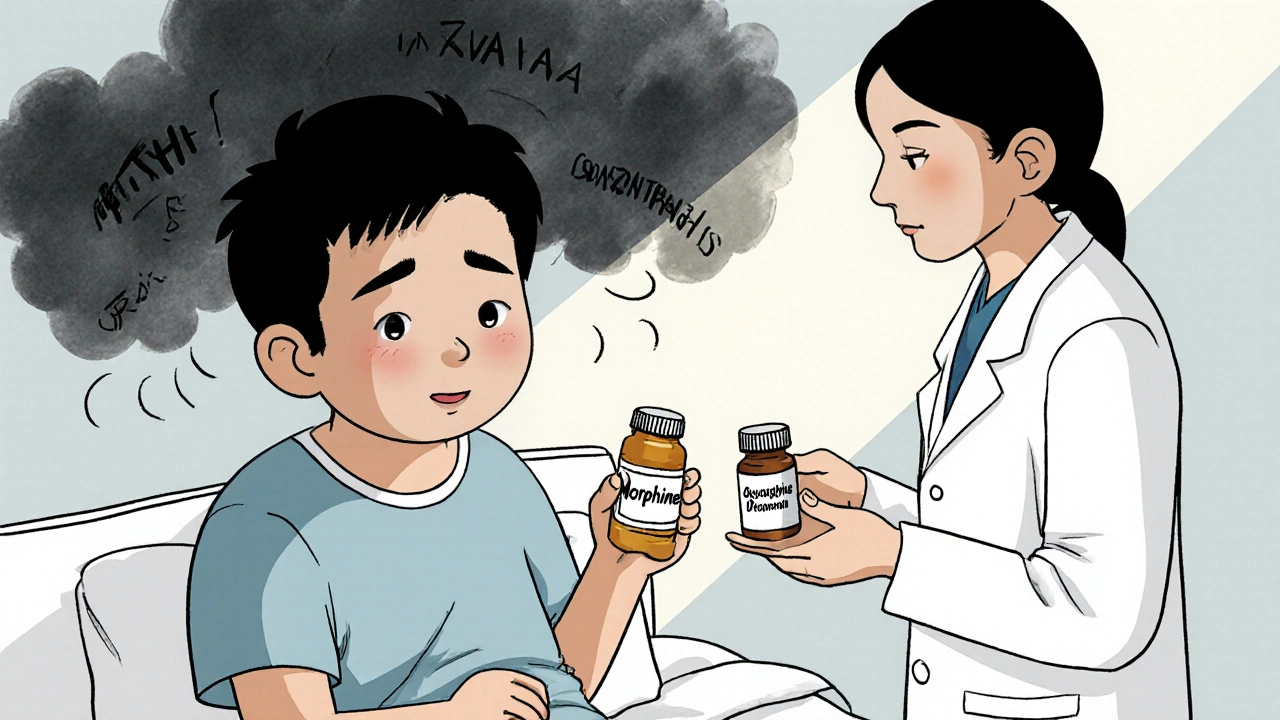

Which Opioids Work Best for Reducing Side Effects?

Not all opioids are created equal. Some are better than others at avoiding certain side effects. For example:- Oxycodone often causes less nausea and constipation than morphine. Many patients switch to oxycodone and notice they can eat again or stop feeling foggy.

- Fentanyl (especially as a patch) avoids the digestive system entirely, which helps with nausea and stomach issues. It’s a good option if you’re struggling with vomiting or gut motility problems.

- Methadone is different. It doesn’t just replace another opioid-it often lets you take less. Studies show patients on methadone frequently reduce their total daily opioid dose, even while maintaining pain control. That’s because methadone works on more than one pain pathway and lasts longer in the body. But here’s the catch: methadone’s dosing isn’t straightforward. The old rule of thumb-10 mg of morphine equals 1 mg of methadone-is outdated. New data suggests the real ratio might be closer to 9:1 or even higher, especially if you’re switching because of side effects, not pain. Getting this wrong can be dangerous.

There’s no universal "best" opioid for everyone. It depends on your body, your symptoms, and your history. That’s why rotation isn’t a DIY decision. It needs careful planning.

The Safety Trap: Why Dose Conversion Matters

Switching opioids sounds simple: just swap one pill for another. But it’s anything but. Your body doesn’t instantly adjust. Even if you’ve been on morphine for months, your system doesn’t fully recognize oxycodone or methadone as the same thing. That’s called incomplete cross-tolerance. That’s why experts always recommend reducing the new opioid’s starting dose by 25% to 50%. Why? To avoid overdose. If you just use a standard conversion table and give the full equivalent dose, you could end up with respiratory depression-slowed or stopped breathing-which can be fatal. For example, if you’re on 60 mg of morphine per day, a standard conversion table might say you need 20 mg of oxycodone. But a safe start would be 10-15 mg, then adjust slowly over days or weeks. This is where many mistakes happen. Clinicians who don’t follow this rule put patients at risk.Why Methadone Is Different-and Risky

Methadone is powerful, long-lasting, and unpredictable. It stays in your system for up to 60 hours, unlike most other opioids that clear in 6-12 hours. That means if you take it once a day, it keeps building up. Add another dose too soon, and you could overdose days later. It also changes how your body processes other drugs. If you’re on methadone and start a new antibiotic or antidepressant, your methadone levels can spike without warning. That’s why switching to methadone should only happen under close supervision, often in a pain clinic or with a specialist. But here’s the upside: when done right, methadone can cut your total opioid dose by 30% to 50% while keeping pain managed. For someone struggling with constipation, fatigue, or mental fog, that reduction can feel life-changing.

What You Should Track After the Switch

Switching opioids isn’t a one-time fix. It’s a process. You need to monitor your body’s response. Here’s what to track for at least two weeks after the change:- Pain levels (use a 0-10 scale daily)

- Sleep quality

- Appetite and digestion

- Energy levels and mental clarity

- Any new side effects-dizziness, itching, sweating, mood changes

Write it down. Bring it to your next appointment. If your pain is worse or side effects haven’t improved, you and your doctor may need to try another switch. If things are better, you’ve found a better fit.

What’s Not Being Said: The Evidence Gap

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: there are no large, randomized trials proving opioid rotation works better than staying on one drug. Most of the evidence comes from small observational studies-tracking patients over time, not testing against a control group. The 2009 guidelines from the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management are still the gold standard. They’re over 15 years old. No major update has replaced them. That doesn’t mean the practice is outdated-it means we’re still learning. Researchers are now looking at genetic testing to predict who will respond best to which opioid. Imagine a simple blood test that tells you: "Morphine will make you nauseous. Try oxycodone instead." That’s the future. Until then, rotation remains a clinical art, guided by experience and cautious science.What to Ask Your Doctor

If you’re thinking about switching opioids, don’t wait until you’re miserable. Ask these questions:- "Is my side effect likely caused by this specific opioid?"

- "What’s the plan for reducing my dose safely during the switch?"

- "Will you use a conversion ratio that accounts for incomplete cross-tolerance?"

- "Are you considering methadone? If so, will you monitor me closely during the first few weeks?"

- "How will we know if this switch is working? What signs should I watch for?"

Your voice matters. If you feel dismissed or rushed, seek a second opinion. Pain management isn’t one-size-fits-all. You deserve a plan that treats your whole life-not just your pain score.

Is opioid rotation safe?

Yes, when done correctly under medical supervision. The biggest risk is overdose from incorrect dosing during the switch. That’s why doctors always start with a lower dose of the new opioid-usually 25% to 50% less than the calculated equivalent. Never adjust your dose on your own.

Can opioid rotation help with constipation?

Yes. Some opioids, like morphine, are more likely to cause severe constipation. Switching to oxycodone, fentanyl (patch), or methadone often improves bowel function because they affect the gut differently. Many patients report regular bowel movements after the switch.

How long does it take to see results after switching?

It varies. Some people feel better within a few days, especially with nausea or drowsiness. For pain control and full side effect relief, it usually takes 1 to 3 weeks. Methadone can take longer-up to 5 to 7 days just to reach steady levels in your blood.

Does opioid rotation mean I’ll need higher doses long-term?

Not necessarily. In fact, many patients end up on lower total doses, especially if they switch to methadone. The goal isn’t to increase your opioid use-it’s to find a better fit so you can manage pain with fewer side effects and possibly less medication overall.

Can I switch opioids on my own if my current one isn’t working?

No. Opioid rotation requires precise calculations and monitoring. Self-switching can lead to overdose, withdrawal, or dangerous drug interactions. Always work with your doctor or pain specialist. Even if you feel frustrated, never change your medication without professional guidance.

10 Comments

This is why people die. Someone reads a blog and thinks they can swap opioids like swapping coffee brands. 25% reduction? More like 50% if you're dumb enough to trust a Reddit post over a pharmacist.

bro i switched from morphine to oxycodone and suddenly i could eat again?? like i wasn't just a zombie with a stomach full of cement. also my dog started wagging his tail when i walked in the room. that's how bad it was.

I am from India and we don't have easy access to these options. But I know someone who switched to methadone and his pain went down, his energy went up. It's not magic, but it's hope. Talk to your doctor, don't give up.

The pharmacokinetic variability across CYP450 substrates is non-trivial, particularly when considering incomplete cross-tolerance dynamics. The 25-50% reduction protocol is grounded in CYP3A4/2D6 metabolic heterogeneity, yet clinical adherence remains suboptimal. Methadone’s prolonged half-life necessitates TDM, especially with polypharmacy.

STOP GIVING PEOPLE FALSE HOPE. You think switching opioids is some magic fix? 😤 You're just trading one hell for another. I went from morphine to methadone and ended up in the ER because my doctor used a "standard table". 🤬 Now I'm addicted to a drug that lasts 3 days and I can't even sleep. You people are reckless.

I read this and I thought - this is what happens when Western medicine treats pain like a math problem. You don’t fix a broken soul with a pill swap. You need yoga. You need chai. You need to sit with your pain, not run from it. But no, let’s just keep dosing until we find the perfect chemical cocktail. 🤡

I switched to fentanyl patch last year and it changed my life. No more nausea, no more constipation, and I could finally play with my kids without feeling like I was underwater. I know it sounds crazy, but it worked. Don't give up on finding your fit.

The empirical underpinnings of opioid rotation remain, regrettably, anecdotally derived; a patchwork of clinical intuition masquerading as evidence-based practice. One is left to wonder whether the paradigmatic shift from morphine to oxycodone constitutes a therapeutic advance-or merely a rebranding of pharmacological desperation.

I did the methadone switch and it was rough for the first week... but now? I'm actually functioning. Like, I went from 0 to 6 on the energy scale. My wife said I started laughing again. I didn't know I'd forgotten how. 🙏

I must emphasize, with the utmost gravity, that opioid rotation-while potentially beneficial-is not a trivial intervention; it demands meticulous calculation, vigilant monitoring, and an unwavering commitment to patient safety. To treat this as a casual adjustment is not merely irresponsible-it is a profound dereliction of duty.

Write a comment