Stroke Mood Prediction Tool

Brain Lesion Location & Mood Predictor

Select the brain area affected by stroke to see typical mood changes, frequency, and onset.

Stroke is a sudden disruption of blood flow to the brain, either from a blockage (ischemic) or a bleed (hemorrhagic). It can damage neurons, alter brain chemistry, and trigger a cascade of physical and mental challenges.

Emotional regulation refers to the brain's ability to monitor, evaluate, and modify emotional responses so they fit the situation. When the brain areas that manage mood are injured, the system goes off‑balance.

Why Emotion Takes a Hit After a Stroke

About 30‑40% of stroke survivors report new‑onset mood problems within the first six months. The reason isn’t just grieving a loss of function; it’s a literal change in the hardware that runs our feelings.

- Lesion location matters. Damage to the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, or limbic pathways often leads to irritability, flat affect, or anxiety.

- Neurotransmitter imbalance. Stroke can lower serotonin and dopamine levels, the chemicals that keep mood stable.

- Inflammatory response. The body’s immune reaction releases cytokines that have been linked to depressive symptoms.

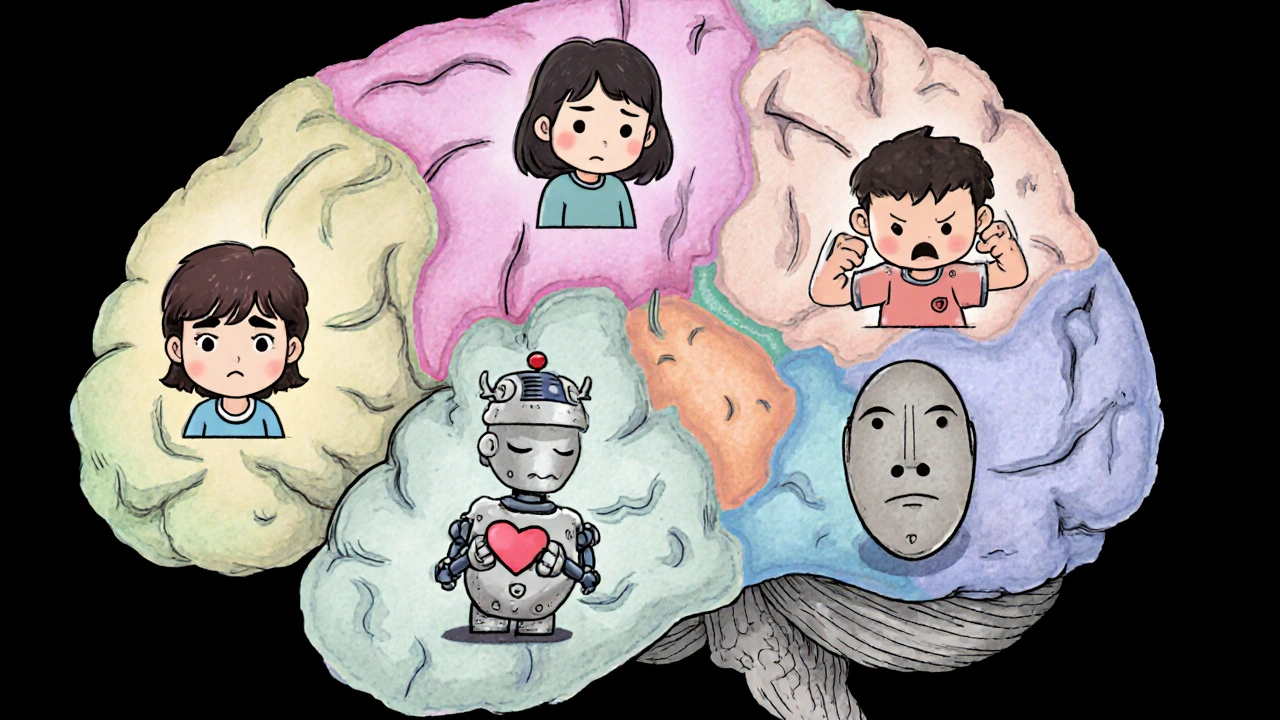

Brain Regions and Their Mood Roles

Understanding which part of the brain was hit helps predict emotional outcomes.

| Brain Area | Common Mood Change | Frequency | Typical Onset |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left frontal lobe | Depression, low motivation | 30‑45% | Weeks‑months |

| Right frontal lobe | Irritability, emotional lability | 25‑35% | Days‑weeks |

| Temporal lobe (amygdala) | Heightened anxiety, fear | 20‑30% | Immediate‑early |

| Basal ganglia | Apathy, reduced affect | 15‑25% | Weeks‑months |

| Brainstem | General emotional flattening | 10‑15% | Variable |

Common Emotional Disorders After Stroke

Three disorders dominate the post‑stroke landscape.

- Post‑stroke depression (PSD). Affects roughly one‑third of survivors. Symptoms range from persistent sadness to loss of pleasure in previously enjoyed activities.

- Post‑stroke anxiety (PSA). Often co‑occurs with PSD but can appear alone. Common worries include fear of another stroke and doubts about independence.

- Emotional lability (often called pseudobulbar affect). Sudden bouts of laughing or crying that seem out of proportion to the situation.

These conditions aren’t just “in the head.” They correlate with slower physical recovery, longer hospital stays, and higher caregiver stress.

Assessing Mood Early and Often

Screening tools make it easier for clinicians to catch problems before they spiral.

- Patient Health Questionnaire‑9 (PHQ‑9). A nine‑item survey that quantifies depressive severity.

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder‑7 (GAD‑7). Mirrors the PHQ‑9 but for anxiety.

- Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI). Captures a broader range of emotional and behavioral changes.

Ideally, these tools are administered at discharge, 1‑month, 3‑month, and 6‑month milestones.

Therapeutic Strategies That Work

Because the problem is both neurological and psychological, a blended approach yields the best results.

Medication Management

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as sertraline have the strongest evidence for reducing PSD. For patients with significant anxiety, a low‑dose SSRI combined with a short course of benzodiazepine (for acute phases only) can be effective.

Rehabilitation‑Based Interventions

Two rehab techniques directly target emotional regulation.

- Cognitive‑behavioral therapy (CBT). Helps patients identify negative thought patterns and replace them with realistic alternatives. When delivered in groups, CBT also builds a peer support network.

- Mindfulness‑based stress reduction (MBSR). Teaches awareness of the present moment, which can temper emotional overreactions caused by a hyper‑reactive amygdala.

Physical Activity

Exercise releases endorphins and boosts dopamine. Even low‑intensity walking programs, when done consistently, lower PHQ‑9 scores by an average of 3‑points.

Family and Caregiver Involvement

Caregivers often notice mood shifts before clinicians do. Training families to use supportive communication, validate feelings, and avoid “negative reinforcement” reduces relapse rates.

Practical Tips for Survivors and Loved Ones

Here are day‑to‑day actions that keep mood in check.

- Maintain a regular sleep schedule. Poor sleep magnifies emotional volatility.

- Track mood changes in a journal. Patterns can help clinicians pinpoint triggers.

- Stay socially connected. Virtual meet‑ups or stroke support groups combat isolation.

- Limit alcohol and caffeine, especially in the first three months.

- Set realistic goals for daily tasks; celebrate small wins to boost self‑efficacy.

When to Seek Professional Help

If any of the following occur, reach out promptly:

- Persistent sadness lasting more than two weeks.

- Thoughts of self‑harm or hopelessness.

- Sudden, uncontrollable episodes of laughing or crying.

- Severe anxiety that interferes with sleep or medication adherence.

Early intervention shortens recovery time and improves overall quality of life.

Future Directions in Research

Scientists are exploring new ways to protect emotional circuits during acute stroke care.

- Neuroprotective drugs. Agents that stabilize serotonin receptors are in Phase II trials.

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). Targeted magnetic pulses to the left prefrontal cortex have shown promise in reducing PSD.

- Digital phenotyping. Wearable devices that monitor speech tone and activity levels could warn of mood declines before they become clinically apparent.

Key Takeaways

- Stroke often disrupts stroke emotional regulation by damaging brain regions that manage mood.

- Depression, anxiety, and emotional lability affect up to 40% of survivors.

- Lesion location predicts the type of mood change; left‑frontal damage leans toward depression, right‑frontal toward irritability.

- Regular screening with PHQ‑9, GAD‑7, and NPI catches problems early.

- A combo of SSRIs, CBT, exercise, and caregiver support offers the best chance for emotional recovery.

How soon after a stroke can mood changes appear?

Mood changes can show up within days, especially emotional lability tied to right‑frontal lesions. Depression usually emerges weeks to months later as the brain’s chemistry settles.

Can antidepressants be used safely with stroke medications?

Yes, most SSRIs have minimal interaction with common antiplatelet or anticoagulant drugs. However, clinicians monitor for bleeding risk, especially with drugs like sertraline.

Is emotional lability the same as depression?

No. Emotional lability (pseudobulbar affect) causes sudden, involuntary laughing or crying, while depression is a sustained low mood. Both can coexist, though.

What role do caregivers play in managing post‑stroke mood?

Caregivers spot early mood shifts, enforce medication schedules, and provide emotional validation. Training them in supportive communication reduces relapse rates by up to 20%.

Are there non‑pharmacologic options that work as well as medication?

In mild‑to‑moderate cases, CBT combined with regular exercise can match the efficacy of SSRIs. Severe depression still often needs medication plus therapy.

11 Comments

They’re using SSRIs as a cash cow for pharma while ignoring the real brain‑injury roots.

It’s irresponsible to downplay the emotional fallout of a stroke; survivors deserve more than a quick prescription.

The brain isn’t a machine you can patch with a pill and call it a day.

We must push for holistic care that respects the person’s dignity.

Ignoring the psychological scars is a betrayal of the oath to do no harm.

Oh, look, another checklist of meds and therapy.

Yeah, you can throw CBT into the mix and hope the mood magically steadies, but most folks are just trying to remember how to button a shirt.

The real trick is letting patients know it’s okay to feel crappy for a while.

A little humor, a steady walk, and a supportive buddy can keep the gloom from turning into a permanent cloud.

If you think a smile will cure a lesion, you’ve been watching too many sitcoms.

Totally. I’ve seen people pretend they’re fine just to avoid being a burden, and it only makes the anxiety worse.

I totally get how overwhelming all these terms can feel, especially when you’re already coping with physical rehab.

One thing that helped me was keeping a simple mood diary – just a few bullet points each day about what felt good or bad.

Even if you think it’s “just a phase,” tracking patterns can give your doctor clues about triggers.

Don’t forget to ask your therapist about mindfulness exercises; they’re low‑key but surprisingly effective for calming that hyper‑reactive amygdala.

And if you’re lucky enough to have a supportive family, let them know exactly what you need – sometimes a gentle reminder to take a walk or a hug can do more than any questionnaire.

Sleep hygiene is another hidden hero – a regular bedtime can make the emotional swings a lot less jagged.

Lastly, reach out to a local stroke survivor group; sharing stories with people who truly understand can cut the isolation down to almost nothing.

It’s not a magic cure, but these small steps add up to a steadier mood over time.

We can’t keep glossing over the fact that many clinicians treat post‑stroke mood issues as an afterthought, as if the brain’s chemistry is a simple switch.

Patients deserve a full‑spectrum plan that respects both body and soul.

Leaving them with only a prescription feels like moral negligence.

When we demand comprehensive care, we uphold the dignity they earned through their struggle.

From an Indian perspective, community support is as vital as any medication.

Families often gather around the survivor, sharing chai and stories, which naturally lifts mood.

Combining that with structured physiotherapy creates a powerful synergy.

Don’t underestimate the cultural cushion – it can be a game‑changer for emotional recovery.

Ugh, the drama of sudden tears at the grocery store is *so* real 😭.

But hey, at least the therapist gets a good story for the group chat 😂.

Every small victory, like a longer walk, is a step toward brighter days.

Seeing the link between lesion location and specific mood changes helps a lot when planning rehab.

Right‑frontal damage often brings irritability, while left‑frontal lesions lean toward depression.

Knowing this can guide both medication choices and therapy focus.

When we talk about post‑stroke emotional regulation, we’re really confronting the philosophy of identity itself – what makes you, you, when the neural circuits that underlie feeling are disrupted?

The brain, after all, is not just a biological organ but a narrative engine that weaves experiences into a coherent self.

If a stroke severs the pathways that normally temper anger, joy, or sadness, the narrative fragments, leaving the survivor to grapple with a sense of incompleteness.

This fragmentation can be likened to a novel whose chapters are shuffled; the story still exists, but the flow is broken.

Therapeutically, this is why interventions like CBT are more than symptom‑targeted; they aim to reconstruct the story, offering scaffolding for new connections.

Meanwhile, mindfulness practices act as a pause button, granting the mind a moment to observe the disordered emotions without being swept away.

Pharmacology, especially SSRIs, can be viewed as a gentle editor, smoothing out harsh tonalities, but it should never replace the author’s voice.

Physical activity, too, writes its own sub‑plot, releasing endorphins that can brighten the overarching theme.

Family members become co‑authors, shaping the narrative through validation, encouragement, and gentle correction of maladaptive beliefs.

When caregivers learn to recognize early mood shifts, they provide the feedback loop essential for narrative cohesion.

Research into neuroprotective agents and TMS is, in effect, attempting to preserve the original manuscript before the pages are torn.

Digital phenotyping, with its continuous monitoring, promises a future where the story’s deviations are caught before they become permanent edits.

All of these approaches converge on a single principle: emotional health after stroke is not merely the absence of pathology, but the presence of a reintegrated, meaningful self.

In practice, this means clinicians must balance the scientific with the humane, treating the brain’s chemistry while honoring the person’s lived story.

Only then can we hope to guide survivors back to a narrative where they recognize themselves as whole, resilient protagonists.

Write a comment