Drug Metabolism Interaction Checker

Check Your Medication

Imagine taking a medication that’s supposed to help you feel better-only to end up with severe nausea, dizziness, or worse. For some people, this isn’t bad luck. It’s genetics. Your body’s ability to process drugs isn’t the same as your neighbor’s. And that’s where genetic testing for drug metabolism comes in.

What Is Pharmacogenetic Testing?

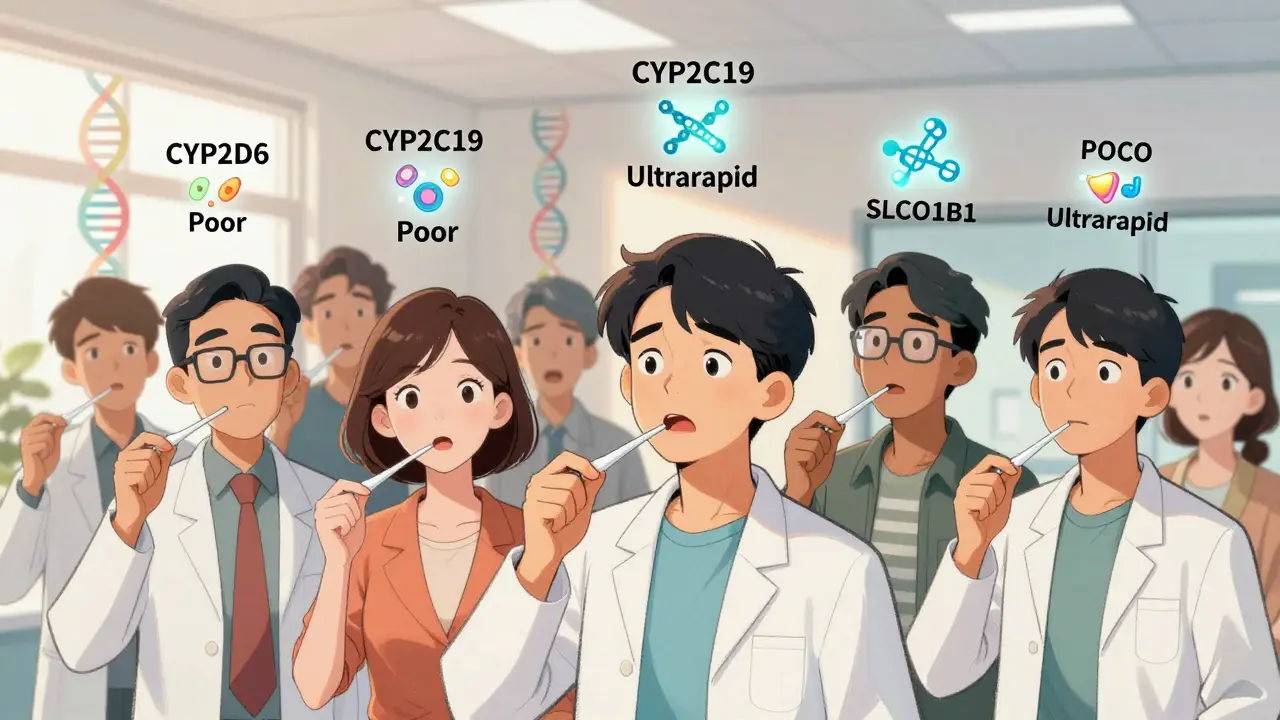

Pharmacogenetic testing looks at your DNA to see how your body breaks down medications. It checks specific genes that control enzymes responsible for metabolizing drugs. The most common ones are CYP2D6, CYP2C19, DPYD, and SLCO1B1. These genes tell your liver whether to process a drug slowly, normally, or too fast. That directly affects how well a drug works-and whether it causes side effects.For example, if you’re a poor metabolizer of CYP2D6, common antidepressants like fluoxetine or codeine might build up in your system and cause toxicity. On the flip side, if you’re an ultrarapid metabolizer, those same drugs might not work at all because your body clears them too quickly.

This isn’t science fiction. It’s happening in clinics right now. The FDA tracks over 300 drug-gene interactions in its official database. Some of these are so well-established that testing is standard before prescribing certain drugs-like HLA-B*57:01 testing before giving abacavir to HIV patients. That test prevents a life-threatening allergic reaction that used to happen in 5-8% of people. Now, thanks to genetic screening, it’s almost zero.

Which Medications Can Be Affected?

Not every drug needs genetic testing. But for some, it makes a huge difference. Here are the big ones:- Warfarin (blood thinner): Too much can cause dangerous bleeding. Too little won’t prevent clots. Genetic variants in CYP2C9 and VKORC1 help doctors pick the right starting dose.

- Clopidogrel (antiplatelet): Used after heart attacks or stents. If you’re a poor CYP2C19 metabolizer, this drug doesn’t activate properly. Your risk of another heart event jumps by 50%.

- SSRIs and SNRIs (antidepressants): CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 variations affect how well drugs like sertraline, escitalopram, and venlafaxine work. A 2022 JAMA study showed testing cut inappropriate prescriptions by 30% in depression patients.

- 5-Fluorouracil (chemotherapy): People with DPYD gene mutations can have deadly reactions to this common cancer drug. Testing prevents hospitalizations and deaths.

- Statin drugs (cholesterol): SLCO1B1 variants increase the risk of muscle pain and damage. Knowing your status lets your doctor choose a safer statin or lower dose.

That’s just a handful. Out of more than 1,500 commonly prescribed drugs in the U.S., only about 300 have clear genetic guidance. But the list is growing.

How Does the Test Work?

Getting tested is simple. No needles, no fasting. Most labs use a cheek swab-just rub a cotton stick inside your mouth for 30 seconds. Some use a blood sample. The sample goes to a lab, and in 3 to 14 days, you get a report.The results classify you into one of five metabolic categories for each gene:

- Poor metabolizer

- Intermediate metabolizer

- Normal (extensive) metabolizer

- Rapid metabolizer

- Ultrarapid metabolizer

Your result doesn’t say “don’t take this drug.” It says, “Here’s what your body is likely to do with it.” That helps your doctor adjust the dose or pick a different drug entirely.

For example, if you’re a poor CYP2D6 metabolizer and need pain relief, your doctor might skip codeine (which needs CYP2D6 to work) and choose acetaminophen or tramadol instead. No trial and error. No side effects from guesswork.

What Are the Real Benefits?

The biggest win? Avoiding bad reactions.A 2022 study in JAMA followed 1,100 people with depression. Half got genetic testing before starting antidepressants. The other half got standard care. The tested group had 30% fewer prescriptions with known drug-gene conflicts. They also reported fewer side effects in the first 8 weeks.

Another study looked at statin users who had muscle pain. Those who got SLCO1B1 testing and switched meds had a 60% adherence rate after three months. The group without testing? Only 33% kept taking their pills.

And then there’s the cost angle. Preventing one case of abacavir hypersensitivity saves around $37,000 in hospital bills. The test costs $200. That’s not even close to a fair trade.

People with mental health conditions are especially interested. A NAMI survey found 58% of users who’d had bad drug reactions would get tested if they could. Why? Because they’re tired of feeling worse from the meds meant to help them.

What Are the Limits?

It’s not magic. And it’s not perfect.First, not every gene-drug pair has strong evidence. CYP2D6 and tamoxifen, for example, used to be heavily promoted for breast cancer patients. But later studies showed the link isn’t as clear as once thought. The American Academy of Family Physicians says many commercial tests overpromise.

Second, genetics isn’t everything. Age, liver health, other medications, diet, and even gut bacteria affect how drugs work. A genetic test gives you part of the picture-not the whole story.

Third, results can be confusing. About 15-20% of tests show “variants of uncertain significance.” That means: we found a change in your DNA, but we don’t know what it does. That can cause anxiety-and no clear action.

And then there’s access. Most insurance plans only cover testing for specific drugs, like abacavir or 5-fluorouracil. For everything else, you’re paying out of pocket. Prices range from $250 to $500. That’s a barrier for many.

Who Should Consider It?

You don’t need to get tested just because you can. But here are situations where it makes strong sense:- You’ve had a bad reaction to a medication-even if it was years ago.

- You’re starting a drug with a known genetic risk (like clopidogrel, warfarin, or certain antidepressants).

- You’re on multiple medications and keep having side effects.

- You have a family history of adverse drug reactions.

- You’re starting cancer treatment or long-term psychiatric meds.

If you’re healthy, on one medication, and doing fine? Testing probably won’t change anything. But if you’ve been through the medication roulette-trying one drug, then another, then another-this could be the missing piece.

What Happens After the Test?

The test isn’t the end. It’s the start of a conversation.Your doctor needs to understand your results. But here’s the problem: only 35% of primary care doctors feel confident using this data. That’s why some people get tested, get a report, and then their doctor says, “I don’t know what to do with this.”

That’s why it helps to work with a specialist-like a clinical pharmacist, genetic counselor, or a provider in a system with built-in decision support. Places like Mayo Clinic and Vanderbilt have integrated genetic data into their electronic health records. When a doctor prescribes a drug, the system flags if your genes suggest a risk.

If your provider doesn’t know how to use the results, ask for a referral. Or bring the report to a pharmacist who specializes in pharmacogenomics. Many specialty pharmacies now offer free consultations with your results.

Is It Worth It?

If you’ve struggled with medication side effects, or if you’re about to start a high-risk drug, yes-it’s worth it.It’s not a crystal ball. But it removes guesswork. It turns trial and error into informed decisions. For people with depression, heart disease, or cancer, it can mean the difference between feeling better and feeling worse.

The field is still growing. More drugs will get genetic labels. More insurers will cover testing. More doctors will learn how to use it.

Right now, the strongest cases are clear: avoid deadly reactions, improve adherence, and stop wasting time on drugs that won’t work for you. That’s not just science. It’s common sense.

If you’re considering it, talk to your doctor. Ask if your medication is on the FDA’s pharmacogenomic list. Ask if your health system offers testing. And if cost is a barrier, look into programs through research hospitals or specialty pharmacies-they sometimes offer discounts or payment plans.

You wouldn’t drive a car without knowing how the engine works. Why take a drug without knowing how your body will handle it?

Is genetic testing for drug metabolism covered by insurance?

Insurance coverage depends on the drug and your plan. Medicare and most private insurers cover testing for specific high-risk drugs like abacavir, 5-fluorouracil, and warfarin. For other medications, coverage is rare unless your doctor proves medical necessity. Out-of-pocket costs range from $250 to $500 for comprehensive panels. Some labs offer financial assistance programs.

Can genetic testing tell me exactly which drug to take?

No. It doesn’t give you a prescription. Instead, it tells your doctor how your body is likely to process certain drugs. That helps them choose safer options or adjust doses. For example, if you’re a poor metabolizer of CYP2D6, your doctor might avoid codeine and choose ibuprofen instead. But they still need to consider your full health picture.

How long do test results last?

Your genes don’t change. Once you’re tested, the results are valid for life. You don’t need to retake the test. Keep a copy of your report and share it with any new provider, especially before starting a new medication. Some people store results in apps like MyPharmGKB or keep a printed copy in their health file.

Are at-home genetic tests like 23andMe useful for drug metabolism?

Not reliably. While 23andMe and similar services report some pharmacogenetic variants, they’re not clinically validated for medical use. Their reports lack context, clinical guidelines, and support from healthcare professionals. For medical decisions, use a test ordered by a provider through a CLIA-certified lab. Clinical tests are designed for accuracy and actionability.

Can genetic testing prevent all bad drug reactions?

No. Genetics is only one factor. Drug interactions, liver or kidney disease, age, and other medications also play a role. Testing reduces risk-but doesn’t eliminate it. That’s why it’s used alongside clinical judgment, not as a replacement. It’s a tool, not a guarantee.

8 Comments

I had no idea my bad reaction to fluoxetine was genetic. I thought I was just 'not a pill person.' This makes so much sense now. I’ve been on 5 different antidepressants and each one either didn’t work or made me feel like I was drowning in slow motion. If I’d known this earlier, I could’ve saved years of misery.

My mom got tested after a scary reaction to warfarin. The results changed everything. They switched her to apixaban and she’s been fine for 3 years now. Simple test, huge payoff.

Let me be perfectly clear: this isn't 'personalized medicine'-it's lazy prescribing. Doctors have been using trial-and-error for decades because they refuse to learn basic pharmacology. Now they're outsourcing their incompetence to a $500 cheek swab? The FDA's database is a mess, and commercial labs are exploiting terrified patients. If you're getting tested, demand peer-reviewed evidence for each gene-drug claim-or don't bother.

Wait, so if I get tested, does that mean my doctor will finally stop ignoring my side effects? Or will they just say 'it's in your genes' and move on? I’ve been screaming for years that my meds make me feel like a zombie. Nobody listens. Now I’m supposed to pay $400 so they can say, 'Yep, you’re a poor metabolizer' and still give me the same drug? 😒

Big Pharma loves this. They’re pushing genetic tests so they can patent new versions of old drugs that 'work better' for your DNA. Meanwhile, the real solution-lower doses, natural alternatives, and actual doctor-patient time-is buried under $$$ and corporate jargon. 23andMe told me I’m a slow CYP2D6 metabolizer… but my doctor won’t even look at it. 🤡 #PharmaControl

Let me tell you, this entire pharmacogenomic movement is nothing short of revolutionary-nay, epoch-defining. I mean, we’re talking about the very architecture of human biochemistry being decoded to optimize pharmaceutical efficacy. My cousin’s oncologist used DPYD testing before her chemo regimen, and she didn’t end up in the ICU like her sister did in '19. The fact that insurance still balks at covering this is a moral travesty. I’ve compiled a 47-page annotated bibliography on this topic. Would you like it? I can email it. I’ve even written to my congressperson. We must demand universal access. This isn’t science fiction. It’s science fact. And it’s being suppressed.

If you’ve ever been on meds that made you feel worse, this is worth a look. Not because it’s perfect, but because it gives you a fighting chance. No more guessing. No more 'try this, if that doesn’t work, try that.' You deserve better than that. Talk to your doctor. Bring the article. Ask for the test. You’ve got nothing to lose but the side effects.

My sister got tested after 7 years of depression cycles. They found she was an ultrarapid CYP2C19 metabolizer. Switched her to vortioxetine. Within 3 weeks, she slept through the night for the first time in a decade. 🙌 I cried. This isn’t just science-it’s hope. And yes, it’s expensive. But so is losing years of your life. I’m saving up for my own test. You’re not alone.

Write a comment