Bladder Infection Risk Assessment Tool

Assess Your Risk of Permanent Urinary System Damage

This tool estimates your risk of developing long-term complications from bladder infections based on your medical history and treatment patterns. Early intervention is key to preventing permanent damage.

When a bladder infection (cystitis) occurs, it’s an inflammation of the bladder lining caused by bacteria entering the urinary tract, many people wonder if that short‑term irritation can scar the whole urinary system forever. The short answer is: it can, but only under certain conditions. Let’s break down how a simple infection can turn into a long‑lasting problem and what you can do to keep your urinary health in check.

How a bladder infection starts

The urinary system is a series of hollow organs that move urine from the kidneys to the outside world. It includes the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. In most cases, bacteria from the gut (usually Escherichia coli) hitch a ride up the urethra, multiply in the bladder, and trigger an infection.

- Entry point: The urethra provides the easiest pathway for microbes.

- Growth phase: Warm, moist bladder environment lets bacteria thrive.

- Immune response: White blood cells flood the area, causing pain, urgency, and sometimes fever.

Most of the time, antibiotics clear the bug in a few days and the bladder returns to normal.

When an infection goes beyond the bladder

If the bacteria aren’t stopped early, they can travel up the ureters and reach the kidneys. This escalation is called pyelonephritis. Kidney involvement raises the stakes because kidneys have limited ability to regenerate damaged tissue.

Key risk factors for upward spread include:

- Delayed treatment (more than 48 hours after symptoms appear).

- Underlying urinary tract abnormalities such as vesicoureteral reflux.

- Immunosuppression, diabetes, or pregnancy.

When pyelonephritis occurs repeatedly, scar tissue can form in the renal cortex, reducing kidney function and potentially leading to chronic kidney disease.

Long‑term bladder changes: chronic cystitis and bladder remodeling

Even if the infection stays confined to the bladder, recurring bouts can trigger chronic cystitis. Unlike an acute episode, chronic cystitis is marked by low‑grade inflammation that persists for months.

Scientists have observed three main changes in a chronically inflamed bladder:

- Thickening of the bladder wall (submucosal fibrosis).

- Reduced bladder capacity, leading to frequent trips to the restroom.

- Altered sensory nerves, which can cause pain even after the infection clears.

These changes are often irreversible, meaning the bladder may never return to its original elasticity. For patients with severe fibrosis, surgical interventions such as bladder augmentation become necessary.

Biofilms and antimicrobial resistance: hidden culprits

One reason some infections bounce back is the formation of bacterial biofilms. Biofilms are protective layers that shield bacteria from antibiotics and immune cells. When a biofilm establishes on the bladder wall, even a full course of antibiotics might only suppress symptoms temporarily.

Over time, resistant strains emerge, making future infections harder to treat. This cycle can push a patient into a pattern of repeated, partially treated infections, increasing the odds of long‑term damage.

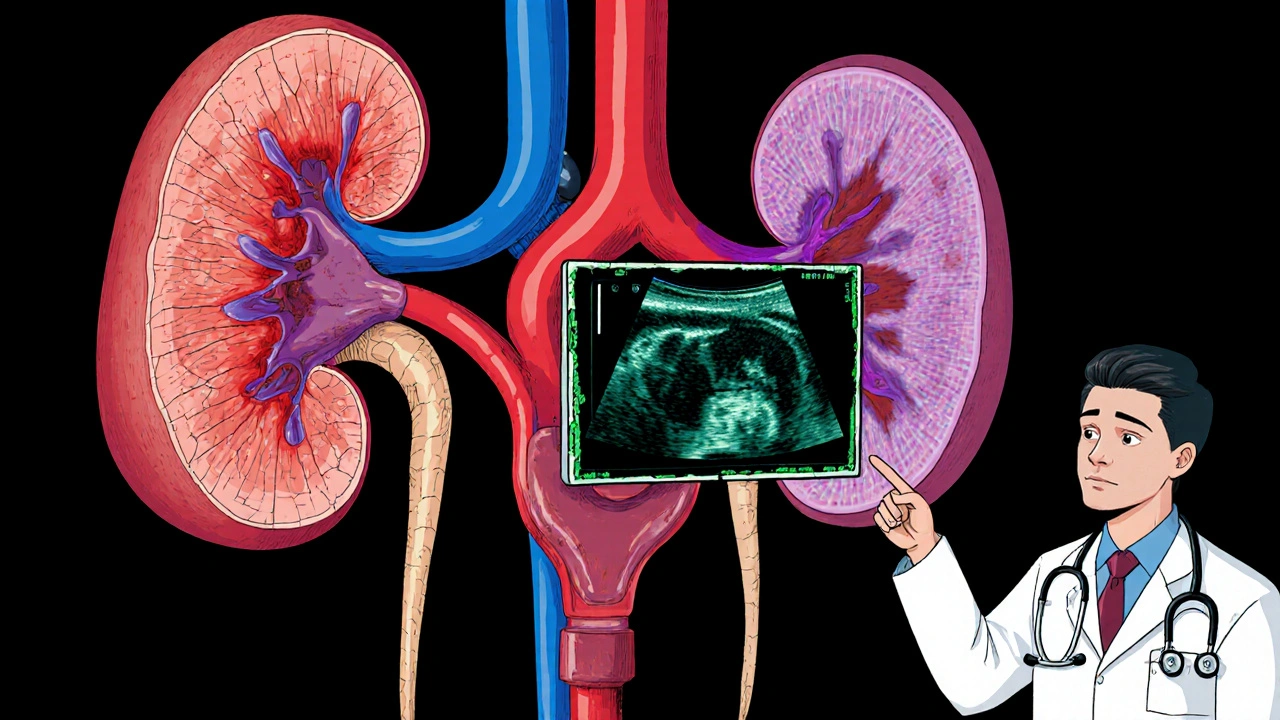

Diagnostic tools to spot early damage

Early detection is crucial. Here are the most reliable tests:

- Urine culture: Confirms the specific bacteria and its antibiotic sensitivities.

- Ultrasound of kidneys and bladder: Detects wall thickening, hydronephrosis, or residual stones.

- CT urography: Provides detailed images of the entire urinary tract, useful for complex cases.

- Urodynamic studies: Measure bladder pressure and capacity, revealing functional impairment.

When any of these tests show abnormal findings, a urologist may recommend a tailored treatment plan to prevent permanent injury.

Prevention strategies that actually work

Stopping a bladder infection before it becomes a chronic problem is easier than fixing the damage later. Follow these evidence‑based habits:

- Hydrate enough to produce at least 1.5 L of urine daily - it flushes bacteria out.

- Urinate soon after intercourse to clear any introduced microbes.

- Avoid irritating feminine products (sprays, douches) that disturb the natural flora.

- Consider prophylactic low‑dose antibiotics if you have more than three infections per year, under a doctor’s supervision.

- Address underlying conditions like diabetes or kidney stones promptly.

When you notice the classic trio of burning, urgency, and cloudy urine, seek medical help within 24 hours. Early treatment dramatically cuts the risk of spreading to the kidneys or forming biofilms.

Potential long‑term complications - at a glance

| Complication | Typical Onset | Impact on Urinary Health |

|---|---|---|

| Kidney scarring (chronic pyelonephritis) | Months‑to‑years of repeated upper‑tract infections | Reduced glomerular filtration rate, potential chronic kidney disease |

| Bladder fibrosis | Persistent or recurrent cystitis over >6 months | Decreased capacity, urgency, incomplete emptying |

| Urinary reflux (vesicoureteral reflux) | Structural damage from chronic inflammation | Back‑flow of urine, higher infection risk, possible renal damage |

| Antimicrobial‑resistant infection | Repeated courses of antibiotics without full eradication | Limited treatment options, higher recurrence rate |

| Painful bladder syndrome (interstitial cystitis) | Chronic irritation with unknown etiology, often post‑infection | Chronic pelvic pain, frequency, and urgency without infection |

What to do if you suspect long‑term damage

Don’t panic, but act fast. Here’s a step‑by‑step plan:

- Schedule a comprehensive urine analysis and culture.

- Ask your doctor for an ultrasound to check bladder wall thickness.

- If kidney involvement is suspected, request a CT urography.

- Discuss the possibility of a urodynamic study if you experience frequent urgency.

- Based on findings, follow a targeted antibiotic regimen, consider prophylaxis, and adopt lifestyle changes.

- Arrange follow‑up imaging in 3-6 months to monitor any reversal of wall thickening.

Most patients see improvement when the underlying infection is fully cleared and preventive measures are in place. However, scar tissue that has already formed may not disappear-early detection is the only way to limit permanent loss.

Key takeaways

- A simple bladder infection rarely causes permanent damage if treated promptly.

- Repeated or untreated infections can lead to kidney scarring, bladder fibrosis, and antimicrobial‑resistant bacteria.

- Diagnostic imaging and urine cultures are essential to spot early signs of long‑term injury.

- Hydration, timely medical care, and addressing risk factors keep your urinary system healthy.

Can a single bladder infection cause permanent kidney damage?

Usually no. A one‑time infection that’s treated within a couple of days rarely reaches the kidneys. Permanent damage becomes a concern only when infections recur or treatment is delayed, allowing bacteria to ascend and cause pyelonephritis.

What symptoms suggest an infection has moved beyond the bladder?

Fever, flank pain, nausea, and blood in the urine are red flags for upper‑tract involvement. If you notice these, seek care immediately for imaging and possibly intravenous antibiotics.

How does a biofilm make bladder infections harder to treat?

Bacteria within a biofilm are encased in a protective matrix that blocks antibiotics and immune cells. This means standard courses may only suppress symptoms, and the infection can flare up later.

Is chronic cystitis the same as interstitial cystitis?

Not exactly. Chronic cystitis is ongoing inflammation due to repeated infections, while interstitial cystitis is a pain syndrome with unknown cause, often occurring after infection but persisting without bacterial presence.

Can lifestyle changes reverse bladder wall thickening?

Early-stage fibrosis may improve with aggressive infection control and hydration, but once dense scar tissue forms, reversal is limited. Preventing further episodes is the key goal.

12 Comments

Look, the microbiology of a bladder infection isn’t some mystical phenomenon; it’s classic uropathogenic Escherichia coli exploiting the urethral conduit, colonizing the urothelium, and triggering a cascade of pro‑inflammatory cytokines. If you ignore the early signs, the bacterial load can ascend, jeopardizing the renal parenchyma. The literature is crystal clear: prompt antimicrobial therapy within 48 hours slashes the risk of pyelonephritis by a factor of three. Delays, on the other hand, give the pathogen time to form biofilm matrices that act like a fortress against beta‑lactams. Moreover, repeated sub‑therapeutic courses seed resistant strains, turning a simple cystitis into a multidrug‑resistant nightmare. So, from a clinical standpoint, a single, well‑treated infection is unlikely to leave permanent scars, but the moment you let it fester, you’re courting chronic cystitis and potential renal scarring.

Wow, who knew drinking water could be a superhero move? 🚰 Just keep peeing after the fun and maybe those bacteria will take a hike. 😂

When you dissect the cascade of events that follows bacterial ingress into the bladder, you quickly realize that it isn’t merely a matter of “a little itch and a burn,” but rather a sophisticated interplay between microbial virulence factors and host immune defenses. The uropathogenic strains possess fimbriae that latch onto uroplakin receptors, establishing a foothold that resists the flushing action of urine. Once attached, they secrete hemolysins and toxins that disrupt the tight junctions of the urothelium, creating micro‑trenches that facilitate deeper penetration. The innate immune system responds with a surge of neutrophils, releasing reactive oxygen species that, while aiming to eradicate the invaders, also inflict collateral damage on the surrounding tissue. This inflammatory milieu stimulates fibroblast activation, laying down extracellular matrix components that, over time, evolve into fibrotic scar tissue. If the infection persists or recurs, the remodeling process accelerates, leading to a stiffened bladder wall with reduced compliance. The subsequent decrease in functional capacity forces the patient into a pattern of frequent voiding, which paradoxically can exacerbate the irritation due to repeated mechanical stress. Moreover, the altered sensory innervation may produce pain signals even after bacterial clearance, a phenomenon often labeled as “post‑infectious bladder pain.” Should the bacteria breach the ureteral junction, they gain access to the renal pelvis, where the limited regenerative capacity of nephrons becomes a critical limiting factor. Repeated pyelonephritic episodes thus sow the seeds of renal cortical scarring, manifesting clinically as a decline in glomerular filtration rate. The presence of biofilm‑encased colonies on the bladder mucosa further complicates therapy, as standard antibiotic regimens may only achieve bacteriostatic effects, allowing the infection to flare once treatment stops. In such scenarios, clinicians must consider combination therapy, extended courses, or even prophylactic low‑dose regimens to suppress the resilient bacterial communities. Ultimately, the key takeaway is that early, aggressive treatment combined with lifestyle measures-adequate hydration, timely voiding, and management of comorbidities-can arrest this cascade before irreversible structural changes set in. Patients who adhere to follow‑up imaging protocols often demonstrate partial reversal of early fibrosis, underscoring the plasticity of the urinary tract when insult is removed. Therefore, vigilance and prompt medical attention remain the cornerstone of preserving both bladder and kidney integrity.

Reading through the mechanisms, I’m reminded how interconnected our bodies are-each small imbalance ripples outward, shaping health in ways we barely notice. The idea that a simple, timely sip of water can tip the scales away from chronic damage feels almost poetic, yet it’s grounded in solid evidence. While the science can be dense, the underlying message is clear: prevention beats cure, every single time.

Yo, if u ignore that drip, u’ll be swimming in pain forever.

It is imperative to acknowledge that the formation of submucosal fibrosis represents a permanent morphological alteration, thereby reducing bladder compliance and necessitating long‑term urological surveillance.

Think of your bladder like a balloon; keep it well‑inflated with water and it stays resilient, but neglect it and the rubber will slowly lose its stretch.

Great rundown, Ivan-let me add a practical angle. In the clinic, we often start patients on a first‑line nitrofurantoin regimen, monitoring for both efficacy and potential pulmonary side effects. If cultures reveal resistance, we pivot to a fluoroquinolone, but only after confirming susceptibility, because overuse fuels the very biofilm problem you described. Imaging isn’t just for the worst‑case; a simple renal ultrasound can catch early hydronephrosis before irreversible damage. For recurrent cases, we sometimes employ a prophylactic low‑dose trimethoprim‑sulfamethoxazole taken at night, which has shown to reduce the frequency of episodes by up to 40 %. Lifestyle tweaks-like avoiding bladder irritants such as caffeine and acidic fruit juices-complement pharmacotherapy. Finally, patient education about timed voiding schedules can train the detrusor muscle, improving bladder emptying and minimizing residual urine, which is a breeding ground for bacteria. All these measures together create a multi‑pronged defense that aligns nicely with the pathophysiological cascade you outlined.

Stay hydrated, listen to your body, and don’t wait too long-your kidneys will thank you! 😊

Corroborating Chirag’s point, quantitative cystometric assessment can delineate detrusor overactivity thresholds, while contrast‑enhanced CT urography provides a high‑resolution map of any subclinical urothelial strictures that might predispose to reflux‑mediated nephropathy.

Look, if you’re not taking that infection seriously right now, you’re basically signing a contract with chronic pain and kidney damage-no one wants that, so act fast.

Exactly-hydration matters; consistency matters; prevention matters!!!

Write a comment